Like chicken tikka, the sarod is a sublime product of the Moghul influence in India. Simon Broughton learns the secrets of the instrument from its leading contemporary virtuoso, Amjad Ali Khan

I first encountered it at the BBC Proms in the Royal Albert Hall in 1994 when a sarod recital at 2am was the finale of a late night concert of Indian music. It was a revelation –Amjad Ali Khan, distinguished and silver-haired, leading a refined journey into musical equivalents of the Taj Mahal, Moghul palaces and hilltop fortresses. Elegance and refinement, supported by a cohesive structure and deep foundations.

The sarod is much smaller than the sitar. It sits comfortably in the player’s lap and is leaner and cleaner in sound, without that predominant jangling of sympathetic strings. The sarod has resonant sympathetic strings, but they are fewer and far less prominent in the soundscape. Still, it’s no less demanding to play. “People like to talk about the king

or prince of sarod, but actually I’m the slave of sarod,” laughs Amjad Ali Khan acknowledging how hard it is to master, yet also confident that no one is likely to outshine him. “I am devoted to it and I always want to try and find out what it wants to say.”

Amjad Ali Khan, born in Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh) in 1945, is the sixth-generation sarod player in his family and his ancestors have developed and shaped the instrument over several hundred years. “You could say it’s my family instrument”, he says with justifiable pride. “Whoever is playing the sarod today learned directly or indirectly from my forefathers.”

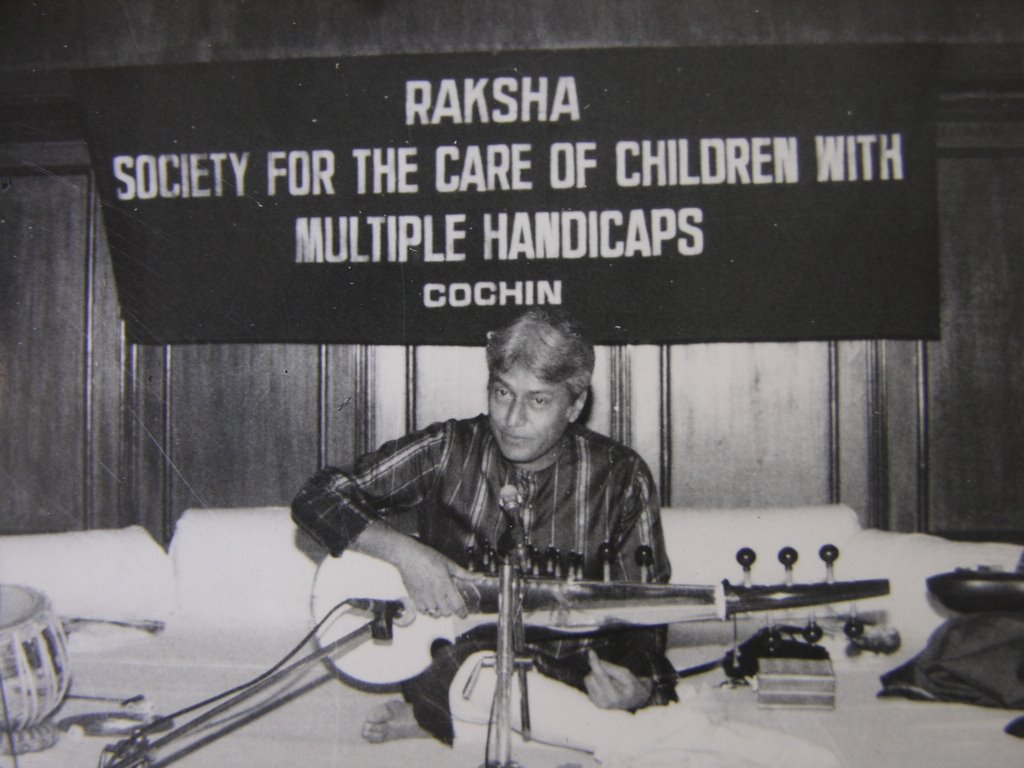

He was all of 6 years old when Amjad Ali Khan gave his first recital of Sarod. It was the beginning of yet another glorious chapter in the history of Indian classical music. Taught by his father Haafiz Ali Khan Amjad Ali Khan was born to the illustrious Bangash lineage rooted in the Senia Bangash School of music. Today he shoulders the sixth generation of inheritance in this legendary lineage.

After his debut, the career graph of this musical legend took the speed of light, and on its way the Indian classical music scene was witness to regular and scintillating bursts of Raga supernovas. Thus, the world saw the Sarod being given a new and yet timeless interpretation by Amjad Ali Khan. Khan is one of the few maestros who consider his audience to be the soul of his motivation. As he once said, "There is no essential difference between classical and popular music. Music is music. I want to communicate with the listener who finds Indian classical music remote."

He has performed at the WOMAD Festival in Adelaide and New Plymouth, Edinburgh Music Festival, World Beat Festival in Brisbane, Taranaki in New Zealand, Summer Arts Festival in Seattle, BBC Proms, International Poets Festival in Rome, Shiraz Festival, UNESCO, Hong Kong Arts Festival, Adelaide Music Festival, 1200 Years celebration of Frankfurt WOMAD Rivermead Festival, UK, and ‘Schonbrunn’ in Vienna.

In the matter of awards, Amjad Ali Khan has the privilege of winning the kind of honours and citations at his relatively young age, which, for many other artistes would have taken a lifetime. He is a recipient of the UNESCO Award, Padma Vibhushan (Highest Indian civilian award), Unicef's National Ambassadorship, The Crystal Award by the World Economic Forum and Hon'ry Doctorates from the Universities of York in 1997, England, Delhi University in 1998, Rabindra Bharati University in 2007, Kolkata and the Vishva Bharti (Deshikottam) in Shantiniketan in 2001. He has represented India in the first World Arts Summit in Venice in 1991, received Hon'ry Citizenship to the States of Texas (1997), Massachusetts (1984), Tennessee (1997), the city of Atlanta, Georgia (2002), Albuquerque, NM (2007)and the Key of the City of Tulsa, Oklahoma and Fort Lauderdale, Miami. April 20th, 1984 was cleared as Amjad Ali Khan Day in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1995, Mr. Khan awarded the Gandhi UNESCO Medal in Paris for his composition Bapukauns. In 2003,the maestro received “Commander of the Order of Arts and letters” by the French Government and the Fukuoka Cultural grand prize in Japan in 2004.

His collaborations include a piece composed for the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Yoshikazu Fukumora titled Tribute to Hong Kong, duets with gutarist Charley Byrd, Violinist Igor Frolov, Suprano Glenda Simpson, Guitarist Alvaro Pierri, Guitarist Barry Mason, Cellist Claudio Bohorquez and UK Cellist Matthew Barley. He has been a visiting professor at the Universities of Yorkshire, Washington, Stony Brook, North Eastern and New Mexico. BBC Magazine had voted one of his recent CDs titled ‘Bhairav’ among the best 50 classical albums of the world for the year 1995. In 1994, his name was included biographically in "International Directory of distinguished Leadership", 5th edition. In 1999, Mr. Khan inaugurated the World Festival of Sacred Music with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. In 1998, Khan composed the signature tune for the 48th International Film Festival.

In 2009, Mr. Khan presented his Sarod concerto Samagam with the Taipei Chinese Orchestra. The same year Amjad Ali Khan was nominated for a Grammy award in the best traditional world music album category. Khan has been nominated for the album 'Ancient Sounds', a joint-venture with Iraqi oud soloist Rahim Alhaj. Recently, the Khans collaborated with American Folk artist Carrie Newcomer at Lotus Arts Festival in Bloomington. On the ninth anniversary of 9/11, Amjad Ali Khan gave a Peace Concert at the United Nations in New York in the presence of the UN Secretary General Ban-Ki-Moon.

He has been a regular performer at the Carnegie Hall, Royal Albert Hall, Royal Festival Hall, Kennedy Center, Santury Hall (First Indian performer), House of Commons, Theater Dela ville, Musee Guimet, ESPLANADE in Singapore, Victoria Hall in Geneva, Chicago Symphony Center, Palais beaux-arts, Mozart Hall in Frankfurt, St. James Palace and the Opera House in Australia.

In his case, the term 'beauty of the Ragas' acquires a special meaning as he has to his credit the distinction of having created many new Ragas.It is love for music and his belief in his music that has enabled him to interpret traditional notions of music for a new refreshing way, reiterating the challenge of innovation and yet respecting the timelessness of tradition.

Two books have been written on him. The first is titled, ‘The world of Amjad Ali Khan’ by UBS Publishers in 1995 and the second, ‘Abba-God’s Greatest Gift to us’ by his sons, Amaan and Ayaan published by Roli Books-Lustre Publications in 2002. A documentary on Mr. Khan called ‘Strings for Freedom’ won the Bengal Film Journalist Association Award and was also screened at the Ankara Film Festival in 1996.

In 2007, Mr. Khan featured in the Southbank Centre’s recently launched the Royal Festival Hall hoardings project ‘Rankin’s Front Row’, where his photograph is included in the frieze that will run the length of the river façade of the Royal Festival Hall. Khan performed at the Central Hall of the Indian Parliament on the commemoration of India's 60th year of Independence in 2007. His concerto for Sarod and orchestra, Samaagam, the result of an extraordinary collaboration with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, is the latest embodiment of his unique ability to give new form to the purity and discipline of the Indian classical music tradition. Samaagam was released worldwide in April 2011 on Harmonia Mundi’s World Village label. In the season 11/12, Amjad Ali Khan was the focus of a 4-concert residency at the Wigmore Hall in London including a new piece with the Britten Sinfonia.

Other highlights include recitals at the Edinburgh International Festival, the Enescu Festival in Bucharest. Recently, he was awarded the Fellowship of the Sangeet Natak Academy. In spring this year Sarod maestro Amjad Ali Khan brought his teaching philosophy to Stanford University this year in a residency titled Indian Classical Music: A Way of Life. As a finale to the Maestro residency, Amjad Ali Khan performed with Maestro Jindong Cai and the Stanford Philharmonia at the Mozart and More Festival.

Married and with two sons, Amaan Ali Khan and Ayaan Ali Khan Ayaan Ali Khanare well known names in the music scene and are the seventh generation of musicians in the family. ‘Coming Masters’ as the New York Times calls them. Amjad Ali Khan's wife Subhalakshmi Khan has been a great exponent of the Indian classical dance, Bharatnatyam, which, she sacrificed for her family. As a soul, so in his heart, he is a man who has proven his indomitable belief in the integration of two of life's greatest forces, love and music. He is a living example of a man who practices that integration each day of his life, both on stage and off stage.

The singing sarod

The instrument speaks eloquently of the close connections between India and Afghanistan and the Persian world. Architecture, food and music a re amongst the great hybrids born of the Islamic invasion of northern India through Afghanistan. The sound of the sarod as we know it today is distinctly Indian in character, but it links to the sinewy, muscular style of the Afghan rabab - a wooden Central Asian lute, covered with skin. For Amjad Ali Khan it’s the tone quality that’s the attraction: “The skin makes the sound very human - it’s not wooden. It has flexibility, sensitivity and depth.” The sound of the sarod is dominated by the singing, vocal tone of its melodic strings. Many instrumentalists - including violinists, clarinettists, sarangi and sitar players - like to compare the sound of their instruments to the human voice. And sarod players are no exception. “I actually spend as much time singing as playing,” admits Amjad Ali Khan and through his father he learned about applying the vocal traditions of dhrupad and khayal to his instrument.

“I am singing through my instrument,” he says. One of the principal modifications of the sarod from the Afghan rabab is its long metal fingerboard, which allows swooping melismatic slides between the melody notes. This is something you can’t do on fretted instruments.

This is a big advantage of the sarod over the sitar”, he explains. “On the sitar you have to pull the string sideways to create the slides. And you can’t pull that far - not more than 3 or 4 notes. But on the sarod you can slide over 7 notes or more, skating up the fingerboard.” As well as this lyrical, vocal style, Amjad Ali Khan is renowned for his fast staccato passages up and down the instrument - something he has made very much his own. This is the latest addition to a long tradition of sarod playing and Amjad Ali Kahn’s two sons, Amaan Ali Khan and Ayaan Ali Khan, are now taking it forward to the next generation. As with the Griots of West Africa, lineage and family are hugely important in Indian music. You wonder what would have happened had one of Amjad Ali Khan’s sons said they were more interested in the electronic keyboard, or accountancy!

The Sarod Lineage

It was Amjad Ali Khan’s great great great grandfather Mohammad Hashmi Khan Bangash, a musician and horsetrader, who came to India with the Afghan rabab in the mid-1700s and became a court musician to the Maharajah of Rewa (Madhya Pradesh). It was his descendants, and notably his grandson Ghulam Ali Khan Bangash who became a court musician in Gwalior, who gradually transformed the rabab into the sarod we know today. The predominantly staccato sound of the rabab was developed into a more lyrical sound with notes that sustained and one of the major instruments of Indian classical music was born. The name sarod comes from the Persian sarood meaning ‘melody’, alluding to its more melodic tone.

Both Ghulam Ali Khan Bangash and his grandson Haafiz Ali Khan received musical tuition from descendants or followers of Miyan Tansen (c1520-1590), one of India’s most celebrated singers and court musician to the great Moghul emperor Akbar, which increases the musical currency of the family no end. The family stayed in Gwalior, Tansen’s city, and no doubt were regular visitors to the holy tamarind tree by Tansen’s tomb said to convey special musical powers. Their musical heritage combines their own school of sarod playing (the Bangash gharana) with the tradition of instrumental music from Tansen (the Senia gharana).

Haafiz Ali Khan - grandson of Ghulam Ali Khan Bangash and father of Amjad Ali Khan – was a very highly respected sarod player and was a court musician in Gwalior up until Independence in 1947. He regularly played for the Maharaja, although Amjad Ali Khan suggests that playing on the whim of a patron who didn’t have a great knowledge or love of music wasn’t an enviable role. Certainly, if you visit the Jai Vilas Palace in Gwalior, the Maharaja’s family home, the over-the-top furnishings, cut-glass Venetian crystal swing and love of Italian Baroque don’t give the impression of a family hugely enamoured of refined sarod music. By contrast, you can also visit the family house where Amjad Ali Khan was born, which he has converted into Sarod Ghar (the ‘Home of the Sarod’) a teaching centre and museum of his family and the sarod, with an impressive collection of instruments including his ancestor’s rababs. Gwalior is actually one of the musical centres of North India. Famous as the home of Tansen, the traditions of dhrupad and khayal music as well as the sarod and there’s an annual music festival in Tansen’s honour. It’s certainly no exaggeration to see Gwalior as an Indian equivalent of Vienna in terms of European music. Indeed Amjad Ali Khan admits that it was visiting Beethoven’s house in Bonn that inspired him to create his Sarod Ghar in Gwalior.

Wood, skin and steel

Some sarods, like the Afghan rabab, are made from mulberry wood, but most are made, like the sitar, from teak. According to Amjad Ali Khan, teak gives a fuller, richer sound. The front of the wooden belly is covered with goat skin. The best place to get goat skins is Calcutta and that’s where most of the sarod makers are based, including Hemendra Chandra Sen, of Hemen & Sons, who is around 80 years old and the most important sarod maker in India. “In Bengal,” explains Amjad Ali Khan, “there is a strong cult of Kali worship and there are lots of sacrifices to her. There are lots of goat skins in Calcutta and that’s why you find most of the tabla makers there too. This is the character of India and its history.

A Hindu woman wears a beautiful Sari made by Muslims in Varanasi. I myself am a Muslim, but I play an instrument made in Calcutta by a Hindu. We all have different religions, but we depend on each other. The history of India is like that.”

It was Amjad Ali Khan’s forefathers that effected the most important development in the instrument and replaced the wooden, fretted neck of the rabab with a smooth polished-steel fingerboard which permits the characteristic slides (or meend) which are used extensively at the beginning of a composition to establish the raga. Just as a tabla player will always have his bottle of talcum powder to sprinkle on his drums, Amjad Ali Khan has a small, decorated box of palm oil to help his left had slide effortlessly around the fingerboard. The rabab’s gut strings have also been replaced by steel ones – piano strings in fact – which give a much more ringing, and singing tone.

There are just four strings used for playing the melody, two drone strings and two chikari strings (raised drone strings which are used to punctuate the melodic phrases with rhythmic accompaniment). Amjad Ali Khan uses 11 sympathetic strings (tuned to the notes of the raga), although other players use more which increases the reverberant effect. The four melody strings are generally tuned (from the top) doh, fa, doh, mi. The lowest string is made from bronze and has a deep, powerful sound, “full of passion”.

The strings are not plucked with the fingers, but with a java or coconut-shell plectrum. “This plectrum can be a hammer or a feather,” says Amjad Ali Khan. “You can play very loud, or give it just a feather touch, skimming gently across the strings.” Actually, the range of colours that a player like Amjad Ali Khan can get out of the instrument is quite incredible and is certainly why it’s found such an important role in classical Indian instrumental music.

Nail-biting technique

Like many musicians who play an instrument that’s been ‘elevated’ from folk to classical status, Amjad Ali Khan can talk quite dismissively of the rabab. “It’s not a very expressive instrument,” he says, “and quite limited.” Using the soft tips of his fingers, he imitates the duller, more gutty sound of the rabab and contrasts it with the clear, ringing tone of the sarod. There are actually two schools of sarod playing – one in which the strings are stopped by the fingertips and the other in which the strings are stopped by the finger-nails of the left hand (as practised by Amjad Ali Khan). This is what makes the clear ringing sound and is one of the things that makes it so difficult to play. “These two nails I never cut,” says Amjad Ali Khan, showing the first and second fingers of his left hand. “They just get worn down. I have to file them after every concert. People might think I am just beautifying my nails, but it’s essential maintenance. They get little grooves cut into them from the strings.”

I get a vivid picture in my mind of the ridges worn into wells in India by the continuous pulling of ropes. It is nails on steel that gives the sarod its clear, muscular sound. “In Hindi we say ‘Swara hi ishwar hay’ - ‘Sound is god’ and whilst you are playing you can feel god. I often have my eyes closed to feel the sound.”

Amjad Ali Khan shows how he can play melodies just using his left hand. “My father used to play like that for five minutes at a time,” he says. “Many years ago, a sarangi player at the court challenged my grandfather. ‘You must play anything that I can play’, he said. My grandfather took up the challenge and copied everything the sarangi player could bow on his instrument. Then my grandfather said: ‘Now you see if you can imitate me’ and asked the sarangi player to tie-up his right hand. My grandfather played beautiful melodies with one hand, but the sarangi player could do nothing without his bowing hand and lost.”

"It was like watching an Indian classical answer to Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker crashing through their favourite Robert Johnson covers at the Cream revival earlier this month. Amjad Ali Khan may be a master of the sarod rather than the guitar,but once he had built up to the crescendo of his solo set - improvising furiously around the melody line with repeated, rapid-fire playing and then letting his equally frantic tabla player take over - it was easy to see why great Indian music can be as exciting as classic blues and rock."

The Guardian, London 2005

"Amjad Ali Khan is the master of the Sarod. Smaller than a sitar, it has 19 strings. Accompanied by his two sons, Amaan Ali Khan and Ayaan Ali Khan, on similar instruments, they created a 57-string three-man symphony orchestra."

The Times, London 2001

"'Imagine a violin virtuoso like Itzhak Perlman also being a direct descendant of Stradivarius, and you can come close to the stature of Indian Sarod master Amjad Ali Khan. Khan is a spiritual, expressive musician, a technically brilliant and inventive player...."

The Inquirer, 2000

"Amjad Ali Khan, who, for many, is god-like in his dramatic powers on the Sarod, delivered his music with the emotional voltage of the blues, and a flexible instrument line that was almost vocal in its expressiveness......."

The Herald, UK (Edinburgh Festival, 2002

For Amjad Ali Khan the sarod is more than an instrument. He is more than a slave and it is more than a master. It is a friend and spiritual companion: “The sarod should have human expression. The sarod should sing, should yell, laugh, cry - all the emotions. Music has no religion in the same way flowers have no religion. Through music – and through this instrument - I feel connected with every religion and every human being – or every soul, I should say.”