Ben Ratliff: …Was your family at all musical?

Sonny Sharrock: No, not instrumentally. My uncle who recently died: He was about five years older than me, he was a singer, and we sang doo-wop back in the '5Os; my brother sang and recorded back in the'5Os, '6Os; other than that, there was no real musical activity in my family.

Ben Ratliff: …Did you record with that group?

Sonny Sharrock: We recorded, but we were very unfortunate: Alan Freed of course was the kingpin, and we got to record in December of '57, but he got busted in the spring of '58, and the record… was never released. The payola thing went down right about that time. … The band we had for our record date was King Curtis on tenor, Kenny Burrell on guitar, Panama Francis on drums . It was a killer band. … I sang baritone and lead, the glory days, did two amateur nights at the Apollo too. Fabulous… I started to listen to jazz about 1957, '58, on a serious level. I had heard some before, but as far as actually going out and buying the records, that was when that started.

Ben Ratliff: Who did you play with when you were starting out as a guitarist in New York? I heard once that you played with Sun Ra for a while.

Sonny Sharrock: I never played with Sun Ra. There is a connection, though. When I first moved to New York, I was living in Harlem with my father, and I was working downtown in an office… One night I got off the train at 125th Street, I lived at 131st, and I bumped into Sun Ra coming around the corner of Seventh Avenue… and I said, "Sun Ra, I want to study with you." So he said, "Okay, come to my house," he gave me his address down on 3rd Street, he said, 'Come on Saturday," so Saturday I went down there. And he showed me two movies, and that was the extent of my relationship with Sun Ra. … One was a movie on his band that he led in Chicago back in the '5Os, a dance band. They were wearing tuxedos and shit. It was really out, man. And the other one was a film on how to make statues sing by vibrating them very fast; you could make stones sing. …So I'm sitting in Sun Ra's living room and he's showing the movies and walking in and out of the room, but in the room is Marshall Allen and Pat Patrick and all of these guys. And at the end of this the phone rings, and it was Olatunji. They had all been working with Olatunji for money, 'cause Sunny was making no money, so he needed a guitar player for a gig the next week, and Pat said, "Oh, there's a guitar player right here. We'll bring him."

Ben Ratliff: …So then you worked with Olatunji.

Sonny Sharrock: Actually, I only did two gigs with Olatunji, but they were spread out over a six-month period, and in the band were all of Sun Ra's guys—Ronnie Boykins, Pat Patrick, Marshall Allen…

Ben Ratliff: And John Gilmore?

Sonny Sharrock: He wasn't one of them, but I ended up doing a trio gig in the Bronx with Gilmore and Johnny Ore, the bass player. We did a couple of weekends up at this club in the Bronx, and it was really very funny. Gilmore's a sweet cat, man, for putting up with my stupidity, 'cause I could hardly play at all. But it was a lot of fun.

Ben Ratliff: When did you really learn how to play?

Sonny Sharrock: I don't know. Did I? [Laughs] I'm still working on that shit, man. I feel that I'm learning now; I'm really starting to play now… I just feel that now I'm starting to play, that I'm in control of what I'm doing on the instrument.

Ben Ratliff: I assume you hooked up with Pharoah Sanders not too long after that.

Sonny Sharrock: Yeah, in '66, I suppose. I was playing with Byard Lancaster, the alto player, in Philly. We had known each other in Berklee, he had set up a series of gigs at this club at the time, a name Philly club, the Showboat, and on Sunday afternoons he was doing these matinees there. I remember that Coltrane had worked the night before in Philadelphia at a concert, so we played Sunday afternoon at this place. So I'm standing there onstage, and I look down, and there's Coltrane, and he'ssmiling at us. It almost killed me, you know. And then I hear this noise behind me, and it was Pharoah. Dave Burrell was sitting in with us, he had been at Berklee with us also, so Pharoah came up, and we played, and the next night I joined his band at Slug's for the Monday-night thing.

Ben Ratliff: Tauhid must have come soon after that.

Sonny Sharrock: We did it that November, and it wasn't released until the next year, I don't think… With him as leader I did two records.

Ben Ratliff: There was also Izipho Zam.

Sonny Sharrock: Yes. I saw it once, a white cover. I saw it once, never heard it.

Ben Ratliff: …You also played with Herbie Mann.

Sonny Sharrock: Yes, for 7 1/2 years, off and on. I'd get fired a lot and come back . …But my influence musically on the band may have been to stretch it out; I remember we ended up doing some Ornette Coleman tunes and we did a couple of my tunes.

Ben Ratliff: …I've also heard that you played on Miles Davis' A Tribute to Jack Johnson.

Sonny Sharrock: Yes, on "Yesternow."

Ben Ratliff: There's no credit.

Sonny Sharrock: A lot of musicians didn't get credit by Columbia for that. The credits I've seen on that record said Billy Cobham on drums, and the date I did was Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland on bass, Chick [Corea], Benny Maupin on tenor…so I don't know if those people get credit either.

Ben Ratliff: Did you do anything else with Miles?

Sonny Sharrock: No…but someone told me that he did listen to me a lot, so that was an influence kind of thing. I was quite proud of that.

Ben Ratliff: …Did you ever play with Albert Ayler?

Sonny Sharrock: No. I used to see Albert and he would say, "Man, we got to play together. I'm trying to put something together," and it never did develop. Then he died.

Ben Ratliff: The way you play often reminds me of him.

Sonny Sharrock: Well, he was a big influence on my playing. Technically, there was a thing he did of playing a note repeatedly and playing it very fast and moving along in a kind of glissando that I adopted from his tenor playing into my playing.

Ben Ratliff: A lot of your themes remind me of his.

Sonny Sharrock: Oh, certainly. Goddamn, that man wrote those diatonic themes based on the pentatonic scale that are just incredible. I was very taken by that.

Ben Ratliff: So you would say that your approach to guitar that you learned during that period was influenced by tenor saxophonists.

Sonny Sharrock: I'm a tenor player, man. I've always thought of myself as one. I don't like guitar, I don't like it at all, and I've always been influenced by horn players.

Ben Ratliff: Why didn't you just pick up the tenor?

Sonny Sharrock: I've got asthma. I did think about it in the beginning when I was going to play, and I'm glad I didn't because I would have tried to sound like Coltrane. I would have tried to become Coltrane. That would not have been good.

Ben Ratliff: So you mean to say that your musical thoughts actually come as tenor-saxophone notes?

Sonny Sharrock: I hear the tenor. Man, those cats were just the best…

Ben Ratliff: When did you start making your own records as a bandleader?

Sonny Sharrock: The first was in '69, Black Woman [Vortex/Atlantic]… that took a lot of nerve, and I think I'm just now becoming a good bandleader. It's a different thing from just playing music. That was a hell of a band, that band, but I wasn't always in control of it. That's what you have to do as a bandleader.

Ben Ratliff: And after that, during the '7Os?

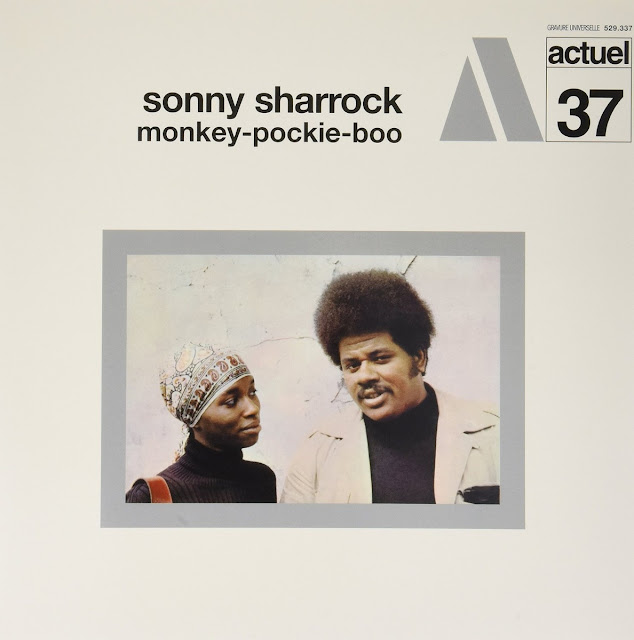

Sonny Sharrock: There were two more records: There was the French one, Monkey-pockie-boo, which I did in Paris at the end of a tour with Herbie Mann… and then the next record was in '75, Paradise, for Atlantic… not a good album. We used a bunch of young cats, it's not their fault that it wasn't a good album, but it's my fault because I couldn't really put the direction together. There was to be another album for Atlantic two years later, but it got scuttled before we got to the studio, and I think it would have been generally the same as Paradise, so it's no big loss… Black Woman was very clear, the focus was extremely clear, then there was the middle period when I was bringing in things from different places that were influencing me, and I was listening to things, but I don't feel that anything really jelled for me again compositionally until I did the solo album [Guitar, recorded in 1986]. So all those years were just spent learning.

Ben Ratliff: Were you listening to any Indian music?

Sonny Sharrock: No. I listened to Indian music when everybody else did. Everyone said Coltrane was listening to Indian music, so we listened to Indian music. I like the food much better. It's a beautiful music, but as far as its application to jazz is concerned, it's limited, like anything you transfer from one setting to another.

Ben Ratliff: … Something that I find nice about your latest records is that nobody knows quite what to call the music.

Sonny Sharrock: I like that too. When we were putting the new record [Live in New York] together in July, the guy who was the assistant engineer at the studio thought it was three different records by three different people.

Ben Ratliff: On Seize the Rainbow, "Dick Dogs" almost sounds like heavy metal, and "The Past Adventures of Zydeco Honeycup" sounds like Booker T. and the M.G.s with a New Orleans second-line beat.

Sonny Sharrock: Yeah, it's a tribute to Professor Longhair. With the last three albums I've done a tune from some great blues or rhythm-and-blues person that I really admire; I've taken a song of theirs and done my thing with it. "Blind Willie" [on Black Woman, and in a different version on Guitar] was for Blind Willie Johnson; that's based on "Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground." On Guitar I did a thing based on "Things I Used to Do" [the Guitar Slim classic], "Black Bottom." And on Rainbow, "Zydeco Honeycup" is based on Professor Longhair's "Tipitina." On the latest one, "Elmo's Blues" [a version of "Dust My Broom"] is actually just straight Elmore James. I feel that that gives me an anchor. There's a tradition on jazz records of doing a blues, you always have to have a blues on every record, so I've just done it that way.

Ben Ratliff: I understand you have a band called the 1954 Rhythm and Blues Revue.

Sonny Sharrock: One day I'm going to record that thing. The last couple of years I've put versions of my group together and backed my vocal group. The concept is to do a total '5Os rhythm-and-blues revue with a big band, but that's extremely hard to get off the ground 'cause it would cost a lot of money. But that's my dream…It would be as big as Alan Freed's shows, man.

Ben Ratliff: What about Last Exit [the touring and recording group with Sonny Sharrock, Peter Brotzmann on saxophones, bassist Bill Laswell, and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson]? Do you see that as a group that will go on for a while?

Sonny Sharrock: …I love those cats, and we always have a good time playing together. After about two weeks I start to need some more structure to what I'm playing. And so I feel a need to come back, but it is a refreshing pause from what I'm usually doing because it's just total abandon. Your responsibility level is a lot lower. In Exit, there is no bandleader, for one thing; you're just responsible for showing up to the gig.

Ben Ratliff: This is really just a musical question: Are you a religious man?

Sonny Sharrock: Yeah, in that I think Coltrane is God. And so is Miles, and Bird, and the rest of those people [laughs]. No, I'm not religious at all; I despise religion, organized religion, and most disorganized religion; I think religion is very dangerous and harmful to people.

Ben Ratliff: I only asked because you did play with a lot of people who considered religion to be important to their music, and you're one of the few people left who still plays somewhat in that vein. ….A lot of your music sounds like it's born out of such calm that it made me wonder.

Sonny Sharrock: It's not a religious thing, but it's based in the religious thing. I know what you're saying, I'm very mindful of the church music that I heard when I was a child, and it's very influential in my music, and it's extremely beautiful and moving… But it's only in a musical sense for me. What they're talking about, you know, I could care less, but their feeling about it moves me. That's about as close as I come to being a religious person, in that musically it's important that that music is so meaningful and so moving.

Ben Ratliff: You hold Coltrane in special regard.

Sonny Sharrock: I listen to Coltrane continually; I listen to Coltrane every day. I try to listen to some of the masters every day.

Ben Ratliff: Who else do you consider to be masters?

Sonny Sharrock: Miles, Bird: They're my favorite masters. Other masters: Louis Armstrong, Duke, Samuel Barber, Ralph Vaughn Williams, Copland… Copland, man, those fuckin' melodies, Jesus!

Ben Ratliff: What about guitarists?

Sonny Sharrock: …When I started playing guitar back in '6O, there was no way to learn, there was nothing, but nowadays you can get "Guitar Player" [Magazine] and you can become a fucking guitar techno-wizard in about three months if you practice every day. One thing about many guitar players is that they take themselves very seriously. That's another reason why I listen so much to the masters: because it's hard to take yourself so seriously when you have these motherfuckers. I think a cat like Al DiMeola would play better if he smiled a little bit. The shit ain't that serious.

Ben Ratliff: What about rock guitar players?

Sonny Sharrock: A cat in Europe gave me a CD of Jimi Hendrix, and that's the first time I ever had any of his music in my house. I never listened to rock players. … Being an improviser myself, I have to be able to remember your solos. If you can come up with a solo like Coltrane's "Favorite Things" or something like that, you're to be remembered. Otherwise, you've done some nice things, that's all well and good, but so have a lot of other people. That's my criterion. I've learned quite a bit from rock players in their use of electronics and the way they use the instrument. …For that they were very important, I think, as far as moving music ahead. But I never listened to them. I wouldn't know one from the other. I never have listened to much guitar, a little classical guitar, that's all.

Excerpts from an Interview with Sonny Sharrock,

WKCR-FM, New York City, 1989, by Ben Ratliff

(printed in the January, 199O program guide, Vol. VI, #4)

Always More in PREPARED GUITAR

Sonny SHARROCK on Improvisation

John Coltrane Interviews

Grant Green interview by Ed Hamilton

Joe Pass Interview 1974

Away from the Big Cities: Morton Feldman interviewed by Jean-Yves Bosseur (November 3, 2015)

Terry Riley Interview (October 20, 2015)

300 essential names in modern guitar through 300 interviews (October 9, 2015)

Interview with Attila Zoller 1/3 (April 10, 2015)

Iannis Xenakis Interview Palais de Mari (March 17, 2015)

Whispering in the Leaves an interview with Chris Watson (February 24, 2015)

Interview with Robert Fripp and Joe Strummer in Musician (February 6, 2015)

Johnny Smith Interview (December 19, 2014)

Glenn Gould Interviews Glenn Gould about Glenn Gould (December 12, 2014)

Marc Ducret Interview with Nate Chinen (December 11, 2014)

Marc Ribot interview by Efren del Valle (December 4, 2014)

Harry Partch Interview 1950 A New Note in music (December 1, 2014)

Tal Farlow Interview (November 28, 2014)

Jim Hall Interview 1996 (November 2, 2014)

Hubert Sumlin Interview by Elliott Sharp (October 15, 2014)

Interview with Wes Montgomery in Crescendo 1965 (October 9, 2014)

Interview with Wes Montgomery in Crescendo 1968 (October 9, 2014)

Michel Henritzi interviewed Otomo Yoshihide (October 2, 2014)

Always More in PREPARED GUITAR

Sonny SHARROCK on Improvisation

John Coltrane Interviews

Grant Green interview by Ed Hamilton

Joe Pass Interview 1974

Derek Bailey

MORE INTERVIEWS in PREPARED GUITAR

Away from the Big Cities: Morton Feldman interviewed by Jean-Yves Bosseur (November 3, 2015)

Terry Riley Interview (October 20, 2015)

300 essential names in modern guitar through 300 interviews (October 9, 2015)

Interview with Attila Zoller 1/3 (April 10, 2015)

Iannis Xenakis Interview Palais de Mari (March 17, 2015)

Whispering in the Leaves an interview with Chris Watson (February 24, 2015)

Interview with Robert Fripp and Joe Strummer in Musician (February 6, 2015)

Johnny Smith Interview (December 19, 2014)

Glenn Gould Interviews Glenn Gould about Glenn Gould (December 12, 2014)

Marc Ducret Interview with Nate Chinen (December 11, 2014)

Marc Ribot interview by Efren del Valle (December 4, 2014)

Harry Partch Interview 1950 A New Note in music (December 1, 2014)

Tal Farlow Interview (November 28, 2014)

Jim Hall Interview 1996 (November 2, 2014)

Hubert Sumlin Interview by Elliott Sharp (October 15, 2014)

Interview with Wes Montgomery in Crescendo 1965 (October 9, 2014)

Interview with Wes Montgomery in Crescendo 1968 (October 9, 2014)

Michel Henritzi interviewed Otomo Yoshihide (October 2, 2014)

.