To be in the silence

Morton Feldman and painting

by Mats Persson

I'm Morton Feldman.

Is there anybody like me?

You know anybody like me?

The minute you call me a composer

you are relating me to someone else.

Pietr Mondrian - Avond (Evening): The Red Tree

1908. Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands

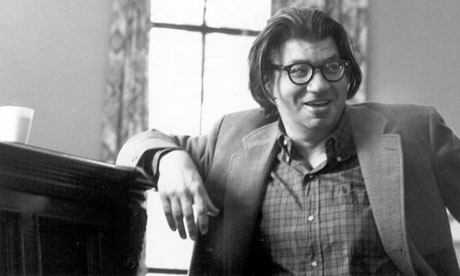

Morton Feldman had an extremely close and intensive relationship to the visual arts. In essays, interviews and in those lectures that were transcribed and preserved, he relates constantly to painting and painters. He focuses mainly upon his friends from the heroic 1950s in New York: Robert Rauschenberg, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston and Mark Rothko, but he also refers to painters such as Piero della Francesca, Cézanne and most of all, to his favorite, Mondrian: If you understand Mondrian then you understand me too. In the beginning I have nothing, in the end I have everything - just like Mondrian - instead of having everything to start with and nothing in the end.(…) I think the big problem is that I have learnt more from painters than I have from composers.

Pietr Mondrian The Gray Tree

1911 Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands

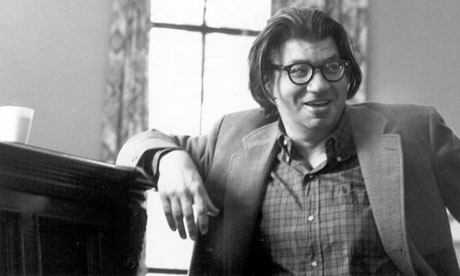

Feldman analyses painting from a very personal point of view; brilliantly and with a phenomenal lucidity. He composes the essays with extreme care, just as he would his music, placing great trust upon his intuition. They have a polemical edge and he never misses a chance to express his aversion for the things he hates the most: the academic avant-garde, Boulez and systematics. Feldman constantly draws parallels between painting and music - mainly his own music - but it is not only the finished painting and composition that he discusses. He is just as interested in comparing painters' work processes with his own. There is a strong sense of show and performance about the lectures and discussions even though they are, of course, looser in form. Feldman is an extrovert entertainer, happily throwing himself between sweeping generalizations, wild analogies and impudent paradoxes. He often seems amazingly self-absorbed, with an arrogance and vanity that can be enervating in the long run and his brutal honesty can sometimes evolve into personal vendetta.

Pietr Mondrian Composition with Grid IX

191 Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands

I have periodically been very absorbed by Morton Feldman's music. I have studied and played most of his piano music and read his texts. I can remember his lectures such as the one at the Musikhögskolan in Stockholm 1968 - he showed slides of his scores, chain-smoking, lighting each cigarette from the butt of the previous one and speaking constantly about time, timing, Beethoven (according to Feldman a master in terms of timing: new ideas, transitions, accents, everything at exactly the right place) and of course, painting.

In the end, however, one is forced to ask oneself the question; what was Feldman's relationship to painting, really? Can it be judged without that painterly ballast, all the analogies and parallels to the visual arts? Or does he perhaps use these comparisons, draping his music upon analyses of his favorite painters as a way of gaining confirmation of its worth? Or is he in fact so directly influenced by artists, their work and way of working that he, consciously or unconsciously, assimilates them and constantly searches for points of correspondence with the visual? Finally, is there a reciprocal communication? Did Feldman and his music influence painting?

Piero della Francesca. Ideal city

c 1470 Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino

There are magical moments in history, moments of intersection, when all factors seem to merge of their own accord and something new and unique appears. The early 1950s in New York was one of these points of intersection. There was a vigorous, bubbling cultural climate, and, especially within art, dance and music, the older values were being questioned and new ground was constantly being discovered. Within painting, it was mainly the abstract expressionists, Pollock, Guston, de Kooning, Rothko and others who were the representatives of the "new" in their work. John Cage, whom Feldman met in 1950 and who knew many of these artists, introduced Feldman to them, many of whom became his friends. This awoke in Feldman an interest for painting; basically, he was fascinated by and perhaps even envied their direct, spontaneous way of working with color on the canvas.

Paul Cezanne. Mill on the River. Watercolor. 1906

Since the middle of the 40s, Feldman had been studying composition privately under the direction of the composer, Stefan Wolpe who, according to Feldman, wanted to create a synthesis of Schönberg and Marx. He was also in contact with Edgard Varèse who, however, was not a teacher in a formal sense. But, said Feldman, I did one lesson on the street with Varèse, one lesson on the street, it lasted half a minute, it made me an orchestrator. He asked: "What are you writing now, Morton?" I told him. He says: "You have to remember the amount of time it takes for the music, when first played on the stage, to go out into the audience, and then go back again." This seemingly simple advice opened Feldman's eyes to the fact that music is all about listening, not structures, systems or calculations but sounds and tones that are projected bodily into space. This insight was of the uttermost importance for Feldman.

Paul Cezanne, Bibemus Quarry.

1900. Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

At the first real meeting between Feldman and Cage, Feldman had a string quartet with him. He showed it to Cage who asked - How have you made this? Feldman answered - I don't really know. Cage started to caper around the room like an ape shouting delightedly - Isn't it fantastic? Isn't it wonderful? It is really beautiful and he doesn't know how he's made it!

Oil on canvas, 72 x 125 x 1 1/2 inches. Collection of the artist.

Cage was living at this time high up in a house with a magnificent view over the East River. It was here, in Cage's flat, that Feldman for the first time received the encouragement and "right" to trust his own musical intuition. It is here that he writes his first graphical composition and for the first time sees and is inspired by Robert Rauschenberg's White Paintings which later were to inspire Cage to write his famous 4'33". Feldman bought his first painting from Rauschenberg, Black Painting, a large picture in which Rauschenberg had pasted newspaper onto the canvas and then painted it black. Feldman asks: What does it cost? - as much as you have in your pocket, replies Rauschenberg. It happened to be 16 dollars plus small change.

Two members of the circle of friends around Cage and Feldman were the pianist John Tudor and the young Christian Wolff, son of the publisher of Kafka who fled with his family from Europe in the early 40s. Christian Wolff - called Orpheus in tennis sneakers by Feldman - composed around this time a sort of minimalistic music using a very restricted tonal material - three or four different pitches. Feldman who always expressed admiration and respect for Wolff's music states that these early pieces by Wolff were very influential upon himself and his music. Feldman later wrote a very good description of Wolff's music - (...) It was certainly more European than Cage's and my own music and by European I mean the connection between concept and poetry (...) He's very conceptual and yet there is a beautiful poetry.

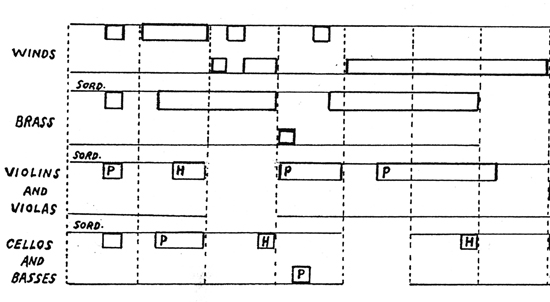

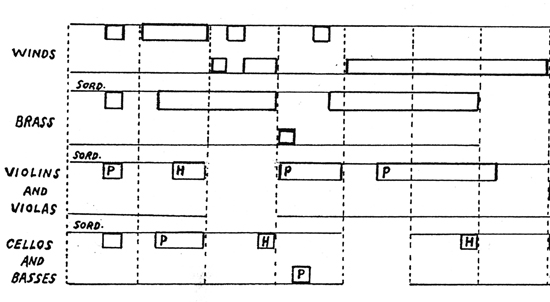

One day in late autumn of 1950, Cage invited Feldman and Tudor to dinner. He cooked unpolished rice which, if cooked properly, takes a very long time. Everyone waited. Feldman went into Cage's workroom and started to draw squares by hand on a piece of paper. Horizontally, one square was the equivalent of a time unit, vertically there were three levels that corresponded to three registers; high, medium and low and the interpreter himself could choose which pitches to place in the respective register. Then he gave certain squares a number which gave the number of tones per time-unit while some squares were left empty. He showed what he had done and Tudor went to the piano and played. It was a revelation for all of them. That one could release music from its melodic and rhythmic straitjacket and allow chance, The Indefinite, to influence the choice of pitch and thereby focus on the sound itself was a total revelation. Cage described later how everything had suddenly changed; a new world had opened up. Cage said to Feldman " you have opened up a new world, let's take a look at what is in it." With the help of this experience and the I Ching, Cage had, within a few days, formed the whole concept of what was to become Music of Changes. Feldman himself quickly composed a series of five pieces for various ensembles - Projections - a strangely delicate and sparse music that was to be performed in a slow tempo and with low dynamics. Already at this point, the sound that was to be characteristic of Feldman was formed. Later, there was to be a series of Intersections - quick pieces with free dynamics - where he further developed his ideas about graph notation.

In my opinion, what is radical in Feldman's new way of working is that he projects the sound in both time and space and thereby in one way fulfils Varèse's vision concerning the acoustic reality of sound as being the raw material of music while in another creates something completely new which, at the same time, parallels abstract expressionism's way of working with color. Feldman liberates sound from traditional gesturing and musical rhetoric and implements the idea of the pure, non-figurative and abstract sound. Feldman himself claims that he was strongly influenced in his graphical compositions by Jackson Pollock's "drip paintings" and his methods of working.

1948. Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, USA

* * *

Feldman knew Pollock's paintings but didn't meet him until 1951. In a wonderful little anecdote, Feldman tells of how, earlier, during his time studying with Stefan Wolpe, he came indirectly in contact with Pollock. Wolpe, who thought Feldman's music was too esoteric, was studying one of his scores one day, talking about the necessity of taking into account the "man in the street" - "Do you never consider the man in the street?" he asked. Feldman was standing by the window and looked out. Who should he see but Jackson Pollock! Since then the man in the street has always been Jackson Pollock for me.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA

In the spring of 1951, Feldman was asked to write some music for the film about Jackson Pollock that Hans Namuth had just completed. Feldman was happy to accept and started visiting Pollock in his studio, way out on Long Island. One thing that surprised Feldman was Pollock's love for Michelangelo, especially his drawings. Pollock admired them for their rhythm, the constantly pumping rhythm. During their conversations, Pollock often talked about his own way of working and the works themselves in relation to other artistic practices such as Michelangelo's drawings or American Indian sand paintings. These kinds of associative connections fascinated Feldman.

In Namuth's film, Pollock describes his own work-process: "I don't work from drawings or color sketches. My painting is direct. I usually paint on the floor. I enjoy working on a large canvas. I feel more at home or at ease on a big area. Having the canvas on the floor I feel nearer, more a part of the painting. In this way I can walk around it, work from all four sides and be in the painting. (...) Sometimes I use a brush but often I prefer using a stick. Sometimes I pull the paint straight out of the can. I like to use a dripping, fluid paint."

Pollock's expression "to be in the painting" came to be of major importance for Feldman. He often used it in essays and lectures as a sign of quality even when analyzing other painters' work. Pollock's way of working from four sides "all over" in order to "be in the painting" meant the suspension of linear thinking. Pollock himself says: "There is no beginning and no end".

Feldman tries at this point to introduce these methods into his own work. He fastens squared paper to the wall and lets each page represent a time-unit without limiting himself to a linear time-scale. He works with the whole composition at the same time without as yet introducing chronological reality: While I'm working, time is frozen. (Beckett says somewhere: "Time changes to Space and there is no Time any longer.")

Like Pollock, Feldman works intuitively. He doesn't follow a plan or system but rather lets intuition steer, step by step. Cage has described how, when composing his graphical scores, Feldman, after fastening his score-sheets to the wall, would back a few paces and regard them as one would a painting and then return to them and change a number here and there until everything "looked good".

Feldman called his score-sheet a time canvas that he attempted to sensitize. I prime the canvas with an overall hue of the music.

Calling the composer's score-sheet a time canvas and comparing it with a painter's canvas is of course paradoxical and an impossibility. In whatever way the score is created, its implementation will be in real time. But despite this paradox or perhaps rather thanks to an insight into its existence, Feldman's work from this point meant a completely new and radical way of thinking. He creates a music that finds itself in the borderlands between the visual and the audio, between time and space, between its construction and its own surface - the sound.

Feldman's new way of thinking was expressed in a couple of pieces composed in so-called open form: an unpublished Intersection for piano and Intermission 6 for one or two pianos from 1953, three years before Stockhausen's famous Klavierstück XI. Intermission 6 consists of one score page with 15 notated and freely placed sounds, from single tones up to 4-part chords. The pianist begins with a freely chosen tone or chord, holding it until it can hardly be heard, moves on to another, any sound at all, and moves freely between the various sounds. In the version for two pianos, the pianists simultaneously describe their own journeys through the score. The dynamics are as soft as possible.

Brown, who, like Feldman, was envious of painters' direct contact with reality - that is to say paint and canvas - also searched for new forms of notation that could establish new relationships between the composer, interpreter and the resulting sound. Alexander Calder's mobiles inspired Brown to find a new form of notation that activated the work's inner changeability during the performance and that could make the music's sound parts change and form new constellations in the same way as the movements of the mobiles created new forms. He wanted to create a notation that allowed for the interpreter's own active, spontaneous and intensive involvement in the creative process corresponding to Pollock's direct contact with the canvas. At the same time, Brown searched for a complexity that could never be notated in a conventional manner.

November '52 and December '52 from Folio are his earliest and perhaps most radical attempts in this direction: two graph scores that have to be freely and spontaneously interpreted by the performer. December '52 can be seen as a two-dimensional reduction of a three-dimensional imaginary space, where the performer is free to move around and transform the graphical symbols into sound.

Alexander Calder. Snow Flurry 1948

Morton Feldman and Philip Guston met at John Cage's home in the early 1950s and came to be close friends. A friendship that lasted almost 20 years. Guston came in contact with Zen Buddhism through John Cage, whom he had known for a number of years. Together, they visited the lectures of the Zen master, D. T. Suzuki. Guston felt that Zen Buddhism offered an alternative to Kirkegaard's categorical either/or choice. Feldman takes up the question in his essay, Neither/Nor, where he claims that the colonization of America by European culture and civilization also meant the inclusion of Kirkegaard's either/or within both politics and art. But suppose what we want is Neither/Nor? Suppose we want neither politics nor art?

On one occasion, when Feldman and Cage were visiting Guston's studio, Cage exclaimed: Good God! Isn't it fantastic that he can make a painting about nothing! Feldman replied: But John, it's all about everything! Both statements are indeed correct which of course fascinated Feldman: Guston - the painter who finds himself between categories and paints everything and nothing at the same time.

In a number of essays during the 1960s, Feldman writes both lovingly and with deep understanding about Guston's abstract painting of the 50s and 60s. It is easy to understand that Feldman felt a strong kinship when looking at Guston's poetical, esoteric and almost weightless paintings. While Feldman writes about them one gets the feeling that he is really writing about his own music.

He often takes his starting-point in Mondrian who, with a utopia in mind, constantly reduces and simplifies, painting himself closer and closer to the square or rather the square's utopia; for Mondrian clarity is the most important quality, so important that he even tries to hide the brush-marks. His pictures, despite often revealing traces of earlier stages, erased contours from earlier variations, look "clean and tidy" from a distance. Close up, the imperfections are visible; perhaps a slightly messy brushstroke where the black blends somewhat with the white. It is this imperfection, in Feldman's view, that gives Mondrian a physical presence; he is there in the painting which should be viewed so close that the edge of the canvas is invisible. In Rothko's case however, brush and canvas are one according to Feldman.

One can see the painting at a distance while at the same time its center disappears. Guston, finally, neither close nor distant, like a fleeting constellation projected on the canvas and then removed, suggests an ancient Hebrew metaphor: God exists but is turned away from us. When looking at a painting by Guston - continues Feldman - it is like seeing two paintings. The play of light between light and dark doesn't happen on the canvas but in the space somewhere between us and the canvas. It is visible only when one sees that it isn't in the painting.

Writing about the famous Attar by Guston that Feldman bought in the 50s he says: I have the feeling that if I moved it to another wall, it would be an entirely different painting. It seems to be reflecting rather than ordinating phenomena. As the tones vibrate, they recede beneath the pigment and return, but with another bowing. In music we would say the sound was sourceless due to the minimum of attack. This explains the painting's complete absence of weight. But the sensation of what you see not coming from what is seen is characteristic of all Guston's work.

As he has done with Pollock and de Kooning, Feldman now searches for points of reference between Guston's way of working and his own. One day Feldman arrived at Guston's studio, they were to go and eat dinner together. Guston was in the middle of painting and didn't want to break off work, so Feldman took a short nap. When he woke up an hour later, Guston was still painting, as if lost within the work, standing so close that it must have been impossible for him to see what he was doing. Just when Feldman awoke it was as if Guston also awoke. He painted a stroke, looked at Feldman and asked with an embarrassed laugh, rather helplessly: - "Where is it?".

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, USA

Guston's sudden awakening, this collision with The Instant, as Feldman calls it, is seen by Feldman as being the first step towards The Abstract Experience - an expression he often uses and one he even refers to in his description of Attar. The Abstract Experience can never be represented. It is never directly visible in a painting but it is, nevertheless, there. (Is it perhaps a kind ofvibrating, lingering personal imprint in the painting, traces of Guston's "being in the painting"?)

Besides analyzing his friend's painting, he also describes his own manner of working and his experiences. As I have mentioned above, Feldman doesn't work according to any predetermined system or idea about construction but rather lets himself be guided by his intuition, step by step, from one sound to the next. He works at the piano in order to be able to constantly weigh the sounds against each other. In this way, he is physically present in the work-process. I think this is his way of, as with the painter, achieving a state of being within the music, the composition. I think there are three things working with me: my ears, my mind and my fingers (...) One of the reasons I work at the piano is because it slows me down and you can hear the time element much more, the acoustic reality.

In 1965, the painter, Mark Rothko, was commissioned to paint a series of gigantic murals for a specially designed building in Houston, Texas - a chapel for meditation and contemplation which came to be called The Houston Chapel. Rothko was also involved in the planning and design of the chapel. He decided upon an eight-sided room with all walls of equal length and the suggestion of an apse towards the north. He hung 14 huge canvases in this room, the walls were almost completely covered and the visitors to the chapel were more or less enclosed inside the paintings. Mark Rothko didn't experience the opening of the Chapel in 1971 - he had taken his own life a year earlier. At the opening, Feldman was commissioned to write a work in memory of Rothko to be performed in The Houston Chapel. The Rothko Chapel for soprano, alto, mixed choir and instruments had its world premier in the Houston Chapel in 1972.

Once again, Feldman attempts to create music that corresponds to the room and the paintings. Rothko's paintings are painted out to the edges of the canvas and in a similar way he tried to make the music permeate the space and not, as in a concert hall, only be experienced from a distance. He distributes the choir and musicians in such a way that they surround the audience. (Viewer/listener is within the paintings/music).

Mark Rothko. Untitled. 1952 - 53

Rothko had long been a member of Feldman's group of friends and especially in the late 60s they grew close. Rothko's huge paintings, vibrating with color, have without doubt had a major influence upon his music. Feldman speaks often of the state of tension and immobility. Stasis - in Rothko's paintings, something he himself sought for in his own music.

Mark Rothko writes: "I paint very big canvases. I'm conscious about the historical function in doing grandiose and pompous paintings. The reason I'm doing it - and this goes for the other painters I know as well - is exactly the opposite: I want to be as intimate and human as possible. To paint a little canvas means that you put yourself outside your own experience, as if you observed an experience through a diminishing glass. When you paint a big canvas you are in it. It's out of your control."

Via the large size of the canvases and the instructions to the viewer to stand close up to them, Rothko is aiming at preventing the viewer from being able to survey the paintings, a survey that hinders a direct experience of them. Feldman sought a similar effect when composing his music, partly by not allowing the structural parts of the composition to stand in simple symmetrical or asymmetrical relation to one another or the whole. In this way he avoids predictability and overview.

The painting and viewing of a large painting involves one interesting aspect: time. At this point I would like to recall another composer/painter relationship: Arnold Schönberg/Vassily Kandinsky.

In one of the interesting letters between the two, written in December 1911, Schönberg writes that he has seen some paintings by Kandinsky. He likes them very much but is bothered by their size. He finds it difficult to appreciate the larger paintings since he cannot get an overall impression of them. The colors sort of slide out of sight and he has to look at the paintings from a distance in order to make them "smaller". Schönberg thinks he could have made the paintings smaller from the beginning while retaining the proportion of the color-tones to each other. He sets up an arithmetic example: If the relationship is: white 120: black 24: red 12: yellow 84 then one can divide by 12 for instance and the relationships become white 10, black 2, red 1, yellow 7 and the picture will be easier to understand!

Kandinsky answers that although 4:2 = 8:4 is mathematically true it is not, artistically. Mathematically 1+1 = 2 but artistically, even 1-1 = 2. He also writes that, using the large size, he deliberately wants to hinder the possibility of a quick overview. Elsewhere, Kandinsky has said that he wanted to introduce a time-element into the viewing of his paintings - that the eye rests first upon the warm colors only then to move on to the colder and less noticeable color forms.

For Pollock and Rothko, the large size of the canvases that hindered an overview was a way of letting the viewer be in the painting - thus stopping time, a total immersion in the present. Kandinsky takes the opposite point of view: he introduces time into his paintings by composing them to encourage the eye to wander within the painting.

Feldman, for whom time is a reality as soon as he composes just one tone, aims at stopping time, firstly through his intuitive way of being "present" within the work and later on - during the last eight years of his life - by composing extremely long pieces, causing the listener to very soon lose his sense of time.

It is not so easy to determine whether Feldman's music influenced painting. It is difficult to give concrete examples of contemporary painters that were influenced by Feldman - it is easier to trace the influence of John Cage, for instance. It is probably as the personal friend and intellectual partner that he has been influential. The creative environment in New York of the 1950's that Feldman was an important member of created unique conditions for the interplay of music and painting. The continuous conversations and discussions that were often to be had at the famous artists-bar, Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village were the basis for a vigorous and fruitful interaction between the arts. John and I would drop in at the Cedar Bar at six in the afternoon and talk with artist friends until three in the morning, when it closed. I can say without exaggeration that we did this every day for five years of our lives.

Feldman's influence upon colleagues and pupils has never been of the kind that has led him to building a "school" - there is no "Feldman-style", his music is far too individual and original. The large number of pupils that he came in contact with during his 15 years as Professor of Composition in Buffalo have developed in a wide range of styles, a sure sign of having had, and in my opinion a criteria for, a good teacher! On the other hand, I imagine that he has been influential on the plane of morals. His courage, consistency and unwillingness to compromise have certainly (or at least it ought to have) influenced his younger colleagues. Among the composers that, in this respect, resemble Feldman I would like to name one: Chris Newman. There is a similar consistency and tenacity to Newman that one finds in Feldman, of whom Newman often expressed an appreciation, even though their expressions were of widely differing characters. While Feldman is slow and soft, Newman has a restless energy and a consistently forte dynamic: every tone has to be carved out with an unrelentless intensity. A strange kind of anti-musician music, beyond all categories of music. It is worth noting that Newman is also an important visual artist.

Morton Feldman's music is paradoxical in many ways. There is a hidden power that can attain provocative heights behind the mellow, sweet-sounding surface. An example would be his graphical compositions from the early 1950's, where the absence of traditional musical conventions such as gesture, phrasing, contrast etc provoke the musical values of the times. This music, as with that of John Cage and Christian Wolff from the same period, can be provocative even today. Another example is the conventionally scored music from the 1950's. Music that borders on the silent, piano pieces in which, as well as being reduced to a minimum, silently depressed keys allows the free strings to resonate, though often extremely quietly. In order to be able to hear, the listener has to sit close to the piano and thus experience an acute shift in perspective: though the resonation of the unplayed strings can be heard, the softly-played tones, the attacks are suddenly strongly felt, unevennesses in touch and sound are distinctly heard and the inner life of the piano, the rustle of the felt on the dampers and hammers, the creaking and squeaking of the mechanical parts and pedals starts to be audible (maybe in a similar way that the "defects" are visible when a Mondrian painting is closely examined?). It is an extremely intimate music that is meant only for very few listeners at one time and almost impossible to record. A music that is full of paradox and is in itself a negation of established forms.

When, as a result of the Midlife Crisis in the early 80's, Feldman starts composing extremely long pieces, he was very unsure as to how these would be received. Much to his amazement, something of a cult came to surround these works, especially in Eastern Europe, often by a young, new audience. Strangely, or rather, significantly, almost none of these large works from the 80's have been performed in Sweden with the exception of a few works for piano. (This astonishing lack of interest also applies to the works of John Cage from the 1970's and 1980's!)

There is an explosive force in this music that the arrangers of concerts seemingly cannot handle: the length of the works, for instance, breaks the bounds of what is a traditional concert. There are forces however that function on other planes. This music, not least because of its provocatively low level of dynamics, demands a concentration and total commitment of the listener, it is a music that is no longer an object that can be described and defined in simple terms or allows itself to be reproduced in the limited form of the CD recording. It is a music that beneath the mellow surface, radically and uncompromisingly, like an antibody, questions and rejects the established music scene, poisoned as it is by conventions and weak compromises.

One cannot say it better than in Christian Wolff's description of his friend, Morty: "One thinks of the disparity of his large, strong presence and the delicate, hypersoft music, but in fact he too was, among other things, full of tenderness and the music is, among other things, as tough as nails."

Morton Feldman and painting

by Mats Persson

A performance of Morton Feldman’s Two Pieces for 3 pianos (1954), by Robert Moran, Loren Rush, and the composer himself.

| The following text is an extended excerpt from the essay written by Mats Persson to accompany his recording, with Kristine Scholz, of Feldman's "Complete works for two pianists", released in 2002 on the Swedish Alice label (ALCD 024). The complete essay (in Swedish and English) is included in the CD booklet. |

I'm Morton Feldman.

Is there anybody like me?

You know anybody like me?

The minute you call me a composer

you are relating me to someone else.

Pietr Mondrian - Avond (Evening): The Red Tree

1908. Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands

Morton Feldman had an extremely close and intensive relationship to the visual arts. In essays, interviews and in those lectures that were transcribed and preserved, he relates constantly to painting and painters. He focuses mainly upon his friends from the heroic 1950s in New York: Robert Rauschenberg, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston and Mark Rothko, but he also refers to painters such as Piero della Francesca, Cézanne and most of all, to his favorite, Mondrian: If you understand Mondrian then you understand me too. In the beginning I have nothing, in the end I have everything - just like Mondrian - instead of having everything to start with and nothing in the end.(…) I think the big problem is that I have learnt more from painters than I have from composers.

Pietr Mondrian The Gray Tree

1911 Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands

Feldman analyses painting from a very personal point of view; brilliantly and with a phenomenal lucidity. He composes the essays with extreme care, just as he would his music, placing great trust upon his intuition. They have a polemical edge and he never misses a chance to express his aversion for the things he hates the most: the academic avant-garde, Boulez and systematics. Feldman constantly draws parallels between painting and music - mainly his own music - but it is not only the finished painting and composition that he discusses. He is just as interested in comparing painters' work processes with his own. There is a strong sense of show and performance about the lectures and discussions even though they are, of course, looser in form. Feldman is an extrovert entertainer, happily throwing himself between sweeping generalizations, wild analogies and impudent paradoxes. He often seems amazingly self-absorbed, with an arrogance and vanity that can be enervating in the long run and his brutal honesty can sometimes evolve into personal vendetta.

Pietr Mondrian Composition with Grid IX

191 Haags Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, Netherlands

I have periodically been very absorbed by Morton Feldman's music. I have studied and played most of his piano music and read his texts. I can remember his lectures such as the one at the Musikhögskolan in Stockholm 1968 - he showed slides of his scores, chain-smoking, lighting each cigarette from the butt of the previous one and speaking constantly about time, timing, Beethoven (according to Feldman a master in terms of timing: new ideas, transitions, accents, everything at exactly the right place) and of course, painting.

In the end, however, one is forced to ask oneself the question; what was Feldman's relationship to painting, really? Can it be judged without that painterly ballast, all the analogies and parallels to the visual arts? Or does he perhaps use these comparisons, draping his music upon analyses of his favorite painters as a way of gaining confirmation of its worth? Or is he in fact so directly influenced by artists, their work and way of working that he, consciously or unconsciously, assimilates them and constantly searches for points of correspondence with the visual? Finally, is there a reciprocal communication? Did Feldman and his music influence painting?

Piero della Francesca. Ideal city

c 1470 Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino

There are magical moments in history, moments of intersection, when all factors seem to merge of their own accord and something new and unique appears. The early 1950s in New York was one of these points of intersection. There was a vigorous, bubbling cultural climate, and, especially within art, dance and music, the older values were being questioned and new ground was constantly being discovered. Within painting, it was mainly the abstract expressionists, Pollock, Guston, de Kooning, Rothko and others who were the representatives of the "new" in their work. John Cage, whom Feldman met in 1950 and who knew many of these artists, introduced Feldman to them, many of whom became his friends. This awoke in Feldman an interest for painting; basically, he was fascinated by and perhaps even envied their direct, spontaneous way of working with color on the canvas.

Paul Cezanne. Mill on the River. Watercolor. 1906

Since the middle of the 40s, Feldman had been studying composition privately under the direction of the composer, Stefan Wolpe who, according to Feldman, wanted to create a synthesis of Schönberg and Marx. He was also in contact with Edgard Varèse who, however, was not a teacher in a formal sense. But, said Feldman, I did one lesson on the street with Varèse, one lesson on the street, it lasted half a minute, it made me an orchestrator. He asked: "What are you writing now, Morton?" I told him. He says: "You have to remember the amount of time it takes for the music, when first played on the stage, to go out into the audience, and then go back again." This seemingly simple advice opened Feldman's eyes to the fact that music is all about listening, not structures, systems or calculations but sounds and tones that are projected bodily into space. This insight was of the uttermost importance for Feldman.

Paul Cezanne, Bibemus Quarry.

1900. Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

At the first real meeting between Feldman and Cage, Feldman had a string quartet with him. He showed it to Cage who asked - How have you made this? Feldman answered - I don't really know. Cage started to caper around the room like an ape shouting delightedly - Isn't it fantastic? Isn't it wonderful? It is really beautiful and he doesn't know how he's made it!

Robert Rauschenberg. White Painting [seven panel], 1951.

Oil on canvas, 72 x 125 x 1 1/2 inches. Collection of the artist.

Cage was living at this time high up in a house with a magnificent view over the East River. It was here, in Cage's flat, that Feldman for the first time received the encouragement and "right" to trust his own musical intuition. It is here that he writes his first graphical composition and for the first time sees and is inspired by Robert Rauschenberg's White Paintings which later were to inspire Cage to write his famous 4'33". Feldman bought his first painting from Rauschenberg, Black Painting, a large picture in which Rauschenberg had pasted newspaper onto the canvas and then painted it black. Feldman asks: What does it cost? - as much as you have in your pocket, replies Rauschenberg. It happened to be 16 dollars plus small change.

Kazimir Malevitch. Suprematist Composition: White on White. 1917

Black Painting became Feldman's companion for the rest of his life. By looking at and studying it, Feldman arrived soon at a new attitude, a desire to make something that was totally unique for him. He didn't see the painting as a collage, it was something more. It was neither life nor art. It was something in-between. Feldman states that it was now that he started to compose music that moved in this in-between state, music that erased the boundaries between material and construction and created a synthesis of method and application. A music between categories.Two members of the circle of friends around Cage and Feldman were the pianist John Tudor and the young Christian Wolff, son of the publisher of Kafka who fled with his family from Europe in the early 40s. Christian Wolff - called Orpheus in tennis sneakers by Feldman - composed around this time a sort of minimalistic music using a very restricted tonal material - three or four different pitches. Feldman who always expressed admiration and respect for Wolff's music states that these early pieces by Wolff were very influential upon himself and his music. Feldman later wrote a very good description of Wolff's music - (...) It was certainly more European than Cage's and my own music and by European I mean the connection between concept and poetry (...) He's very conceptual and yet there is a beautiful poetry.

Mark Tobey. Crystallizations. 1944.

Christian Wolff's piano teacher, Grete Sultan, advised him to study with John Cage. Wolff had a present with him to the first meeting - an English translation of the I Ching - the Book of Changes, that his father had published. This book was to have an enormous influence upon Cage and all of his future work and, at an early stage, was an incitement to the great piano work Music of Changes.One day in late autumn of 1950, Cage invited Feldman and Tudor to dinner. He cooked unpolished rice which, if cooked properly, takes a very long time. Everyone waited. Feldman went into Cage's workroom and started to draw squares by hand on a piece of paper. Horizontally, one square was the equivalent of a time unit, vertically there were three levels that corresponded to three registers; high, medium and low and the interpreter himself could choose which pitches to place in the respective register. Then he gave certain squares a number which gave the number of tones per time-unit while some squares were left empty. He showed what he had done and Tudor went to the piano and played. It was a revelation for all of them. That one could release music from its melodic and rhythmic straitjacket and allow chance, The Indefinite, to influence the choice of pitch and thereby focus on the sound itself was a total revelation. Cage described later how everything had suddenly changed; a new world had opened up. Cage said to Feldman " you have opened up a new world, let's take a look at what is in it." With the help of this experience and the I Ching, Cage had, within a few days, formed the whole concept of what was to become Music of Changes. Feldman himself quickly composed a series of five pieces for various ensembles - Projections - a strangely delicate and sparse music that was to be performed in a slow tempo and with low dynamics. Already at this point, the sound that was to be characteristic of Feldman was formed. Later, there was to be a series of Intersections - quick pieces with free dynamics - where he further developed his ideas about graph notation.

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, gouache, ink

1951. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, UK

In my opinion, what is radical in Feldman's new way of working is that he projects the sound in both time and space and thereby in one way fulfils Varèse's vision concerning the acoustic reality of sound as being the raw material of music while in another creates something completely new which, at the same time, parallels abstract expressionism's way of working with color. Feldman liberates sound from traditional gesturing and musical rhetoric and implements the idea of the pure, non-figurative and abstract sound. Feldman himself claims that he was strongly influenced in his graphical compositions by Jackson Pollock's "drip paintings" and his methods of working.

Jackson Pollock. Number 4 (Gray and Red).

1948. Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, USA

Jackson Pollock1951 Black & White (Number 20)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA

In the spring of 1951, Feldman was asked to write some music for the film about Jackson Pollock that Hans Namuth had just completed. Feldman was happy to accept and started visiting Pollock in his studio, way out on Long Island. One thing that surprised Feldman was Pollock's love for Michelangelo, especially his drawings. Pollock admired them for their rhythm, the constantly pumping rhythm. During their conversations, Pollock often talked about his own way of working and the works themselves in relation to other artistic practices such as Michelangelo's drawings or American Indian sand paintings. These kinds of associative connections fascinated Feldman.

Jackson Pollock. Number 4. 1951

In Namuth's film, Pollock describes his own work-process: "I don't work from drawings or color sketches. My painting is direct. I usually paint on the floor. I enjoy working on a large canvas. I feel more at home or at ease on a big area. Having the canvas on the floor I feel nearer, more a part of the painting. In this way I can walk around it, work from all four sides and be in the painting. (...) Sometimes I use a brush but often I prefer using a stick. Sometimes I pull the paint straight out of the can. I like to use a dripping, fluid paint."

Jackson Pollock Number 2 1951, Collage, Oil

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, USA

Pollock's expression "to be in the painting" came to be of major importance for Feldman. He often used it in essays and lectures as a sign of quality even when analyzing other painters' work. Pollock's way of working from four sides "all over" in order to "be in the painting" meant the suspension of linear thinking. Pollock himself says: "There is no beginning and no end".

Jackson Pollock Number 14, 1951

Tate Britain, London, England, UK

Feldman tries at this point to introduce these methods into his own work. He fastens squared paper to the wall and lets each page represent a time-unit without limiting himself to a linear time-scale. He works with the whole composition at the same time without as yet introducing chronological reality: While I'm working, time is frozen. (Beckett says somewhere: "Time changes to Space and there is no Time any longer.")

Like Pollock, Feldman works intuitively. He doesn't follow a plan or system but rather lets intuition steer, step by step. Cage has described how, when composing his graphical scores, Feldman, after fastening his score-sheets to the wall, would back a few paces and regard them as one would a painting and then return to them and change a number here and there until everything "looked good".

Feldman called his score-sheet a time canvas that he attempted to sensitize. I prime the canvas with an overall hue of the music.

Calling the composer's score-sheet a time canvas and comparing it with a painter's canvas is of course paradoxical and an impossibility. In whatever way the score is created, its implementation will be in real time. But despite this paradox or perhaps rather thanks to an insight into its existence, Feldman's work from this point meant a completely new and radical way of thinking. He creates a music that finds itself in the borderlands between the visual and the audio, between time and space, between its construction and its own surface - the sound.

Feldman's new way of thinking was expressed in a couple of pieces composed in so-called open form: an unpublished Intersection for piano and Intermission 6 for one or two pianos from 1953, three years before Stockhausen's famous Klavierstück XI. Intermission 6 consists of one score page with 15 notated and freely placed sounds, from single tones up to 4-part chords. The pianist begins with a freely chosen tone or chord, holding it until it can hardly be heard, moves on to another, any sound at all, and moves freely between the various sounds. In the version for two pianos, the pianists simultaneously describe their own journeys through the score. The dynamics are as soft as possible.

Letting oneself be influenced by the visual arts and experimenting with form was something that was in the air in the early 1950s. Earle Brown who, despite violent protests from Feldman, was to eventually become a part of the group surrounding Cage, was working with a similar set of problems.

Brown, who, like Feldman, was envious of painters' direct contact with reality - that is to say paint and canvas - also searched for new forms of notation that could establish new relationships between the composer, interpreter and the resulting sound. Alexander Calder's mobiles inspired Brown to find a new form of notation that activated the work's inner changeability during the performance and that could make the music's sound parts change and form new constellations in the same way as the movements of the mobiles created new forms. He wanted to create a notation that allowed for the interpreter's own active, spontaneous and intensive involvement in the creative process corresponding to Pollock's direct contact with the canvas. At the same time, Brown searched for a complexity that could never be notated in a conventional manner.

Alexander Calder. Stainless Stealer. 1966

November '52 and December '52 from Folio are his earliest and perhaps most radical attempts in this direction: two graph scores that have to be freely and spontaneously interpreted by the performer. December '52 can be seen as a two-dimensional reduction of a three-dimensional imaginary space, where the performer is free to move around and transform the graphical symbols into sound.

Mark Rothko. Black on Dark Sienna on Purple, 1960

On one occasion, when Feldman and Cage were visiting Guston's studio, Cage exclaimed: Good God! Isn't it fantastic that he can make a painting about nothing! Feldman replied: But John, it's all about everything! Both statements are indeed correct which of course fascinated Feldman: Guston - the painter who finds himself between categories and paints everything and nothing at the same time.

Philip Guston, Untitled 1950

In a number of essays during the 1960s, Feldman writes both lovingly and with deep understanding about Guston's abstract painting of the 50s and 60s. It is easy to understand that Feldman felt a strong kinship when looking at Guston's poetical, esoteric and almost weightless paintings. While Feldman writes about them one gets the feeling that he is really writing about his own music.

Philip Guston. To B.W.T. 1952

He often takes his starting-point in Mondrian who, with a utopia in mind, constantly reduces and simplifies, painting himself closer and closer to the square or rather the square's utopia; for Mondrian clarity is the most important quality, so important that he even tries to hide the brush-marks. His pictures, despite often revealing traces of earlier stages, erased contours from earlier variations, look "clean and tidy" from a distance. Close up, the imperfections are visible; perhaps a slightly messy brushstroke where the black blends somewhat with the white. It is this imperfection, in Feldman's view, that gives Mondrian a physical presence; he is there in the painting which should be viewed so close that the edge of the canvas is invisible. In Rothko's case however, brush and canvas are one according to Feldman.

Philip Guston. Painting No. 9, 1952

One can see the painting at a distance while at the same time its center disappears. Guston, finally, neither close nor distant, like a fleeting constellation projected on the canvas and then removed, suggests an ancient Hebrew metaphor: God exists but is turned away from us. When looking at a painting by Guston - continues Feldman - it is like seeing two paintings. The play of light between light and dark doesn't happen on the canvas but in the space somewhere between us and the canvas. It is visible only when one sees that it isn't in the painting.

Writing about the famous Attar by Guston that Feldman bought in the 50s he says: I have the feeling that if I moved it to another wall, it would be an entirely different painting. It seems to be reflecting rather than ordinating phenomena. As the tones vibrate, they recede beneath the pigment and return, but with another bowing. In music we would say the sound was sourceless due to the minimum of attack. This explains the painting's complete absence of weight. But the sensation of what you see not coming from what is seen is characteristic of all Guston's work.

Philip Guston, Drawing Related to Zone (Drawing No. 19), 1954

What Feldman is in fact doing is describing his own music and his instrumental sound ideals. With a minimum attack, soft, very soft and as soft as possible are the most common instructions in Feldman's scores, meaning that the tones are played as quietly as possible. He has many times formulated a utopic sound ideal where one cannot hear which instruments are playing - a sourceless sound. As the sound character of an instrument is largely to be found in the attack, it would thus appear that the instructions aim at achieving something as paradoxical as an abstract instrument sound - a sound that is also to be found in Guston's painting.

Philip Guston. Attar. 1953

As he has done with Pollock and de Kooning, Feldman now searches for points of reference between Guston's way of working and his own. One day Feldman arrived at Guston's studio, they were to go and eat dinner together. Guston was in the middle of painting and didn't want to break off work, so Feldman took a short nap. When he woke up an hour later, Guston was still painting, as if lost within the work, standing so close that it must have been impossible for him to see what he was doing. Just when Feldman awoke it was as if Guston also awoke. He painted a stroke, looked at Feldman and asked with an embarrassed laugh, rather helplessly: - "Where is it?".

Philip Guston. Untitled 1949

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, USA

Besides analyzing his friend's painting, he also describes his own manner of working and his experiences. As I have mentioned above, Feldman doesn't work according to any predetermined system or idea about construction but rather lets himself be guided by his intuition, step by step, from one sound to the next. He works at the piano in order to be able to constantly weigh the sounds against each other. In this way, he is physically present in the work-process. I think this is his way of, as with the painter, achieving a state of being within the music, the composition. I think there are three things working with me: my ears, my mind and my fingers (...) One of the reasons I work at the piano is because it slows me down and you can hear the time element much more, the acoustic reality.

Mark Rothko. The Rothko Chapel. 1965-1967

In 1965, the painter, Mark Rothko, was commissioned to paint a series of gigantic murals for a specially designed building in Houston, Texas - a chapel for meditation and contemplation which came to be called The Houston Chapel. Rothko was also involved in the planning and design of the chapel. He decided upon an eight-sided room with all walls of equal length and the suggestion of an apse towards the north. He hung 14 huge canvases in this room, the walls were almost completely covered and the visitors to the chapel were more or less enclosed inside the paintings. Mark Rothko didn't experience the opening of the Chapel in 1971 - he had taken his own life a year earlier. At the opening, Feldman was commissioned to write a work in memory of Rothko to be performed in The Houston Chapel. The Rothko Chapel for soprano, alto, mixed choir and instruments had its world premier in the Houston Chapel in 1972.

Once again, Feldman attempts to create music that corresponds to the room and the paintings. Rothko's paintings are painted out to the edges of the canvas and in a similar way he tried to make the music permeate the space and not, as in a concert hall, only be experienced from a distance. He distributes the choir and musicians in such a way that they surround the audience. (Viewer/listener is within the paintings/music).

Mark Rothko. Untitled. 1952 - 53

Rothko had long been a member of Feldman's group of friends and especially in the late 60s they grew close. Rothko's huge paintings, vibrating with color, have without doubt had a major influence upon his music. Feldman speaks often of the state of tension and immobility. Stasis - in Rothko's paintings, something he himself sought for in his own music.

Mark Rothko writes: "I paint very big canvases. I'm conscious about the historical function in doing grandiose and pompous paintings. The reason I'm doing it - and this goes for the other painters I know as well - is exactly the opposite: I want to be as intimate and human as possible. To paint a little canvas means that you put yourself outside your own experience, as if you observed an experience through a diminishing glass. When you paint a big canvas you are in it. It's out of your control."

Via the large size of the canvases and the instructions to the viewer to stand close up to them, Rothko is aiming at preventing the viewer from being able to survey the paintings, a survey that hinders a direct experience of them. Feldman sought a similar effect when composing his music, partly by not allowing the structural parts of the composition to stand in simple symmetrical or asymmetrical relation to one another or the whole. In this way he avoids predictability and overview.

Mark Rothko. Untitled. 1967.

The painting and viewing of a large painting involves one interesting aspect: time. At this point I would like to recall another composer/painter relationship: Arnold Schönberg/Vassily Kandinsky.

In one of the interesting letters between the two, written in December 1911, Schönberg writes that he has seen some paintings by Kandinsky. He likes them very much but is bothered by their size. He finds it difficult to appreciate the larger paintings since he cannot get an overall impression of them. The colors sort of slide out of sight and he has to look at the paintings from a distance in order to make them "smaller". Schönberg thinks he could have made the paintings smaller from the beginning while retaining the proportion of the color-tones to each other. He sets up an arithmetic example: If the relationship is: white 120: black 24: red 12: yellow 84 then one can divide by 12 for instance and the relationships become white 10, black 2, red 1, yellow 7 and the picture will be easier to understand!

Kandinsky answers that although 4:2 = 8:4 is mathematically true it is not, artistically. Mathematically 1+1 = 2 but artistically, even 1-1 = 2. He also writes that, using the large size, he deliberately wants to hinder the possibility of a quick overview. Elsewhere, Kandinsky has said that he wanted to introduce a time-element into the viewing of his paintings - that the eye rests first upon the warm colors only then to move on to the colder and less noticeable color forms.

For Pollock and Rothko, the large size of the canvases that hindered an overview was a way of letting the viewer be in the painting - thus stopping time, a total immersion in the present. Kandinsky takes the opposite point of view: he introduces time into his paintings by composing them to encourage the eye to wander within the painting.

Feldman, for whom time is a reality as soon as he composes just one tone, aims at stopping time, firstly through his intuitive way of being "present" within the work and later on - during the last eight years of his life - by composing extremely long pieces, causing the listener to very soon lose his sense of time.

Mark Rothko. Untitled. 1967.

It is not so easy to determine whether Feldman's music influenced painting. It is difficult to give concrete examples of contemporary painters that were influenced by Feldman - it is easier to trace the influence of John Cage, for instance. It is probably as the personal friend and intellectual partner that he has been influential. The creative environment in New York of the 1950's that Feldman was an important member of created unique conditions for the interplay of music and painting. The continuous conversations and discussions that were often to be had at the famous artists-bar, Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village were the basis for a vigorous and fruitful interaction between the arts. John and I would drop in at the Cedar Bar at six in the afternoon and talk with artist friends until three in the morning, when it closed. I can say without exaggeration that we did this every day for five years of our lives.

Feldman's influence upon colleagues and pupils has never been of the kind that has led him to building a "school" - there is no "Feldman-style", his music is far too individual and original. The large number of pupils that he came in contact with during his 15 years as Professor of Composition in Buffalo have developed in a wide range of styles, a sure sign of having had, and in my opinion a criteria for, a good teacher! On the other hand, I imagine that he has been influential on the plane of morals. His courage, consistency and unwillingness to compromise have certainly (or at least it ought to have) influenced his younger colleagues. Among the composers that, in this respect, resemble Feldman I would like to name one: Chris Newman. There is a similar consistency and tenacity to Newman that one finds in Feldman, of whom Newman often expressed an appreciation, even though their expressions were of widely differing characters. While Feldman is slow and soft, Newman has a restless energy and a consistently forte dynamic: every tone has to be carved out with an unrelentless intensity. A strange kind of anti-musician music, beyond all categories of music. It is worth noting that Newman is also an important visual artist.

Mark Rothko. Untitled. 1969.

Morton Feldman's music is paradoxical in many ways. There is a hidden power that can attain provocative heights behind the mellow, sweet-sounding surface. An example would be his graphical compositions from the early 1950's, where the absence of traditional musical conventions such as gesture, phrasing, contrast etc provoke the musical values of the times. This music, as with that of John Cage and Christian Wolff from the same period, can be provocative even today. Another example is the conventionally scored music from the 1950's. Music that borders on the silent, piano pieces in which, as well as being reduced to a minimum, silently depressed keys allows the free strings to resonate, though often extremely quietly. In order to be able to hear, the listener has to sit close to the piano and thus experience an acute shift in perspective: though the resonation of the unplayed strings can be heard, the softly-played tones, the attacks are suddenly strongly felt, unevennesses in touch and sound are distinctly heard and the inner life of the piano, the rustle of the felt on the dampers and hammers, the creaking and squeaking of the mechanical parts and pedals starts to be audible (maybe in a similar way that the "defects" are visible when a Mondrian painting is closely examined?). It is an extremely intimate music that is meant only for very few listeners at one time and almost impossible to record. A music that is full of paradox and is in itself a negation of established forms.

Mark Rothko. Untitled. 1968

When, as a result of the Midlife Crisis in the early 80's, Feldman starts composing extremely long pieces, he was very unsure as to how these would be received. Much to his amazement, something of a cult came to surround these works, especially in Eastern Europe, often by a young, new audience. Strangely, or rather, significantly, almost none of these large works from the 80's have been performed in Sweden with the exception of a few works for piano. (This astonishing lack of interest also applies to the works of John Cage from the 1970's and 1980's!)

There is an explosive force in this music that the arrangers of concerts seemingly cannot handle: the length of the works, for instance, breaks the bounds of what is a traditional concert. There are forces however that function on other planes. This music, not least because of its provocatively low level of dynamics, demands a concentration and total commitment of the listener, it is a music that is no longer an object that can be described and defined in simple terms or allows itself to be reproduced in the limited form of the CD recording. It is a music that beneath the mellow surface, radically and uncompromisingly, like an antibody, questions and rejects the established music scene, poisoned as it is by conventions and weak compromises.

Mark Rothko. Untitled. 1969.

One cannot say it better than in Christian Wolff's description of his friend, Morty: "One thinks of the disparity of his large, strong presence and the delicate, hypersoft music, but in fact he too was, among other things, full of tenderness and the music is, among other things, as tough as nails."

sources

http://www.cnvill.net/mfperssn.htm

http://www.wikipaintings.org/

Two Pieces for 3 pianos : Other Minds Audio Archive

Two Pieces for 3 pianos : Other Minds Audio Archive

.jpg)