SECOND PART

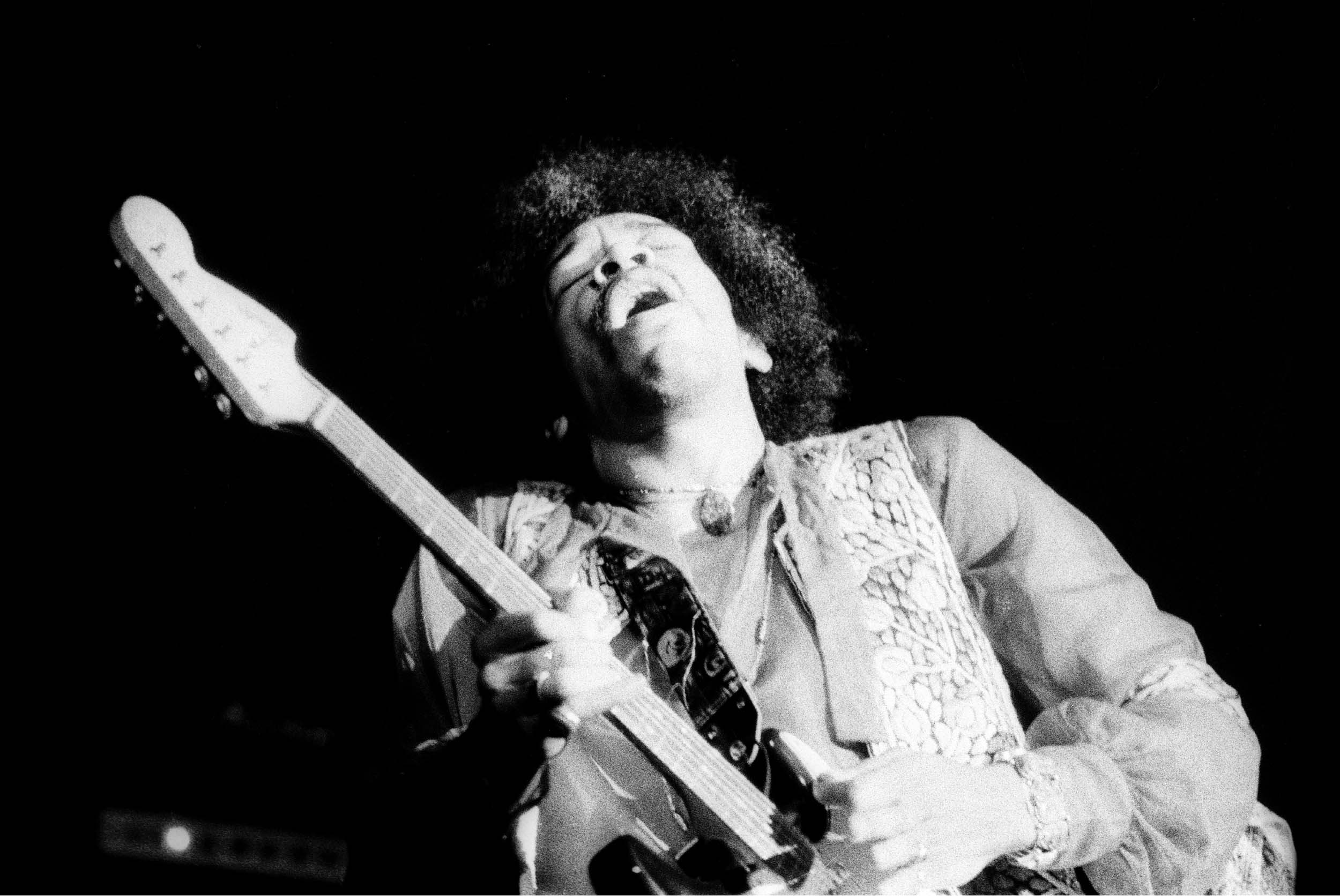

In November 1967, whilst at Keele University, I was involved in the student magazine Unit – edited by Tony Elliott, who was to go on to found Time Out. I suggested a Hendrix piece, as the Jimi Hendrix Experience was due to play at Manchester University Students Union. In the period since the first interview, Jimi had become a megastar and was packing in audiences up and down the country and into Europe. I travelled to Manchester with some friends and we made our way to the gig.

On arriving I found the dressing room packed with people, including Mitch and Noel – but no Jimi. I asked where he was and someone said “Check next door.” I entered the room to find Jimi alone, leaning on a radiator next to a window about fifteen or twenty feet across the room. He looked up and said, “Hello, Steve. How are you?”

I didn’t think much about it at the time, but soon after, on reflection, I appreciated this as the mark of the man. Since I’d met him nine months previously, Jimi had experienced incredible success, fan adulation, and had accrued all the trappings of what was to become “the rock-star lifestyle” – hangers-on, sycophancy, pressure, freely available narcotics, etc. But he still remembered my name and behaved like a perfect gentleman, which is the way I always remember him.

I heard you were in a group in New York with Tim Rose and Mama Cass.

That’s not true. It was another Jimmy. We just happen to have liked “Hey, Joe.” I seen Tim Rose about one time in the Village, for about half a second, and this is after we went back to the States. He tapped me on the shoulder and said [imitates a stoned-sounding voice], “Hi. I’m Tim Rose.” And then he disappears. All this happened within a third of a second. I like his songs, but that’s all I’ve ever seen of him.

What are you trying to do with your new LP?

I really can’t say. It’s very hard to explain your own type of music to somebody. Unless you have a very definite idea of where you’re going, it doesn’t really make any difference which direction you choose, as long as you’re really honest about the songs you write.

What do you think about the commercial pop scene right now?

[Simulates a confused stutter] Well, have you heard the Marmalade and their record “I See the Rain”? I don’t understand why that wasn’t a hit.

Because they have no name and no publicity?

We didn’t have a name when we first started.

But you had the publicity.

But we earned it, though, didn’t we? I think we did. My hair is breaking off now from the hard English water. I’m almost going bald. I guess I used to have it cut much longer.

What level are you aiming for when you make a record – the kids?

No, not necessarily. We quite naturally want people to like it – that’s the reason for putting the record out. You see, I have no taste. I couldn’t say what’s a good record and what’s a bad one, really. We play records at the flat sometimes and say, “This is great,” and then somebody will say, “Oh, yeah, but it’s something else.” Then they say “That’s terrible,” and I’d say, “That’s great – the tremolos, for instance.” [Laughs.] So I don’t have no feeling about commercial records. I don’t know what a commercial record really is. So what we do is write and try to get it together as best as possible for anybody who’d really dig it. It doesn’t make any difference who.

How big a part do visuals play in your stage work?

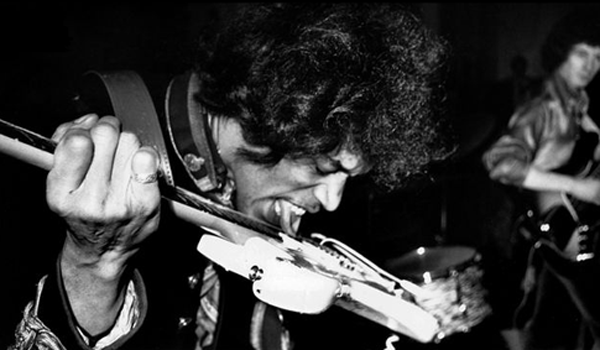

You just do it when you feel like it sometimes. I didn’t feel like leaping about tonight too much. I used to feel I had to do it, but not anymore. Man, you’d have a heart attack if you were doing it every night like we were doing it two or three months ago. We’d be dead by this time. Anyway, you can’t do it right unless you feel it. Half of the things I do I don’t even know it, because I just felt like it at the time. If you have everything planned out and one little thing goes wrong, you think, “Oh, no! What am I supposed to be doing now? Oh, yeah, I’m supposed to be going like this – do do do de do. ‘Hi, everybody. I’m doing it.’” So you’d really be in a world of trouble if one little thing goes wrong.

Do you think you’re a changed person since you came to England?

I didn’t used to talk so much before.

To people like me.

No, that’s alright. [Laughs.] Ho hum. I’m as good as bunnies – and you know how good bunnies are.

Noel Redding: Talk to Mitch. He’s got a very good voice.

What would you think if people went off on you like they do with Dylan?

Jimi: I don’t think about it. Ever since he’s been around, people have been kicking him around, saying, “Oh, man, he sings like a broken-leg dog.”

[At this point, Jill Nicholls from the Manchester Independent asked Jimi the following question] Mr.

Hendrix, is there anything you want materially?

[Noel and other men in the room burst into laughter.] Jimi: Eh?

Is there anything left?

There’s a whole lot of things left – thousands of them. I see them downtown every day. Millions of ’em. Ohh! Marvelous!

Steve: Do you ever think about going back to the States?

I think about it every single day. I really miss it, like the West Coast, because nothing has happened for me. I just like to be out there. I like the weather, the scenery, and some of the people. You can buy a chocolate milkshake in a drugstore, chewing gum in a gas station, and soup from little machines on the road. It’s great, it’s beautiful. It’s all screwed up and nasty and prejudiced, and it’s great and beautiful. It has everything. The same things we hear from there now about the troubles is the same things we hear from Russia – it’s just propaganda, just like Radio Free Europe tells the Russians. [At this point the road manager asks Jimi if he will do a photo shoot, but Jimi continues.] In the States I was playing behind other groups. And for only the first two months before I left the States, we was playing in the Village. I had my own group and we had offers from record companies all over the place, but I don’t think we was ready then. So finally I came over here [to England] with Chas Chandler, with the main ambition to get a group and try to make with something new, whereas in the States I’d been playing behind people like Joey Dee.

What did you think of it?

I don’t dig playing in Top-40 R&B groups. They get feedback in “Midnight Hour.” You can’t do nothing free – everything is completely precise. We came over here with one purpose, and that was to make it. That’s the whole scene. As soon as we start getting behind the times, that’ll be the time to give up. That might be tomorrow evening about 5:45, but we’ll try for as long as possible to keep our own sound, regardless of how it might change. [Jimi notices Steve’s microphone] What a pretty microphone!

Yeah, it’s cute, isn’t it?

Yeah. Thank you!

About Steve Barker

Steve Barker lives in Beijing, China. He produces and broadcasts “On the Wire,” a music show for BBC Radio Lancashire in the UK (www.otwradio.blogspot.com ). He is also the regular dub columnist and contributor for the Wire magazine (www.thewire.co.uk ) and regularly DJs dub sets at clubs in Beijing and Shanghai.

Many thanks to Steve Barker for his kindness.

This Jimi Hendrix interview is ©Steve Barker 2011. Used by author’s permission. All rights reserved. This interview not be reproduced anywhere in any form without Steve Barker’s written permission

More Hendrix in Prepared Guitar