Derek Bailey was interviewed by Henry Kaiser on October 21, 1975 at Bailey’s home in London. The interview was transcribed and edited by Henry Kuntz, with final alterations made by Derek Bailey.

Derek Bailey (Quoting from Edgar Allen Poe): “I found it impossible to comprehend him, even in his moral or physical relations. Of his family I could obtain no satisfactory account. Whence he came I never ascertained, even about his age – there was something that perplexed me in no little degree. There were moments when I should have had little trouble imagining him a hundred years of age. But in no regard was he more peculiar than in his personal appearance. He was singularly tall and thin, he stooped much. His limbs were exceedingly long and emaciated. His forehead was broad and low. His complexion was absolutely bloodless. His mouth was large and flexible and his teeth were more roundly uneven, although sound, than I had ever before seen teeth in a human head. The expression of his smile, however, was by no means unpleasing, as might be supposed, but it had no variation whatever. It was one of profound melancholy, of a phaseless and unceasing gloom.”

Well, this business of playing – to try to put it as briefly as possible: in about 1963-64, I had been a professional musician for about ten years, and I had played more or less every kind of music you can play in order to earn a living. I’d worked in night clubs, dance halls, with country singers, rock singers, folk singers; I had played a bit of jazz. At that time I was also working in studios more than ever. Most of the musics I played were played like any music in the entertainment world. They had quite a lot of improvisation involved in them, or at least some degree of improvisation anyway.

And at that time (1963) I started working with two musicians, a bass player named Gavin Bryars (now a composer) and a drummer, Tony Oxley. They were both much younger than me, and they represented two quite different ways of approaching improvisation. When we played together then, we played sort of a mixture of what was then current jazz. We played as a trio and actually worked together in a night club for a long time. We used to play Bill Evans and Coltrane tunes from their records, and we were interested a lot in Dolphy. It was moving toward a free jazz thing. And over that period, ‘63 – ‘65, we gradually moved from that position of playing these Bill Evans to Coltrane type things to a position of playing completely improvised pieces. And at that point,1965, early ‘66, I don’t know who we were sounding like. We didn’t record anything, we weren’t even the least bit interested in recording. (I find this is one of the things that has changed now. Everyone seems to record everything they play.) Anyway, by the time we’d got to this position of playing completely improvised pieces, I don’t know how you’d identify the music except to say that it was freely improvised.

The main impetus that had got us to this position was a dissatisfaction with the music we were playing – like conventional jazz, music in which we were improvising the idiom. Gavin, though, was a straight musician. His background was completely straight, and later he went to the States and studied with Cage for a while. And it was Gavin’s interest in contemporary composition, which particularly in the early and middle ’60s was involved in improvisation a lot – aleatoric devices, all that stuff – and Tony’s interest in free jazz that led us to the music we played. There were those two avenues which I think have been the two main avenues of the free improvisation situation, and they were in that one group, and that was very useful.

Maarten van Regteren Altena | Derek Bailey | Akademie der Künste, Berlin1978, Workshop Freie Musik. Photo: Gérard Rouy

Now I found as regards the instrument – naturally – that whatever traditional equipment I had on the instrument was no use in these situations. It was no good coming on like Charlie Christian while somebody was playing a gong and somebody else was sawing off the end of the bass. While it might now be perfectly acceptable in Holland to do that (reference to musical humor situations which have become prevalent in Dutch and German improvising -ed) – in fact, it’d bring the house down – there were obvious musical incongruities about this. So as regards to changing the way I played to suit the musical situation, that was how it started. I mean, this went on for years, you understand.

After that, I came to London, and again I was lucky because I met Evan Parker and John Stevens. That was the end of ‘66, and we were playing together through ‘67 and ‘68, and we still play together occasionally. It wasn’t exactly a continuation of the thing I’d been doing with Gavin and Tony, but it was for a while. Then it went more heavily jazz-wise because of certain inclinations that were being expressed at that time, mostly from John. But it was still all improvised, the focus was on playing totally improvised pieces. At least, that’s where I felt the main focus of the music was, regardless of what its affinities might have been whether it was jazz or non-jazz or trying to sound like Stockhausen, or whatever it was doing. It was still necessary, though, to have some sort of language to join in this debate with, and so it was a case of carrying on with the earlier process of trying to develop some way of playing in totally improvised situations.

And after that I was fortunate enough to work with Evan continuously and with a couple of other people who are no longer playing now – drummer Jamie Muir and vocalist Christine Jeffrey. That again was something quite different, but I could view it, as regards playing the guitar, as a further extension of working in a freely improvised situation. In fact, I suppose one of the things all of these stages did was to establish more and more the acceptance of the freely improvised situation and the ways you could work in it and these were really all quite different values. And that lasted until 1970-71. Since then, I’ve worked mainly solo.

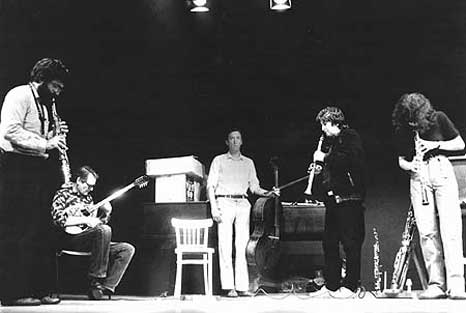

Derek Bailey | Maarten van Regteren Altena | Steve Lacy | Akademie der Künste, Berlin1978, Workshop Freie Musik. Photo: Gérard Rouy

I had been playing solo off and on since 1967, but I found for all sorts of reasons from about 1971 onwards that it was better to concentrate on solo playing. That had to do with a lot of things. One of them was to do with working out this language thing – of this way of playing the guitar. I don’t think of it as a way of playing the guitar, though; I think of it as a way of improvising. It seems to me that whatever I’ve been trying to do on the guitar, for me anyway, it is in order to find a more appropriate way of playing the instrument in a free improvising situation.

Because if you play the guitar, or any other instrument, the way you learn to play it is probably going to be closely associated with some style of music. If, for instance, you’re learning the guitar, you’re going to be learning to play as a flamenco player, or as a jazz player, or you’re going to learn to play finger style. And all the finger style players think that’s the way you play the guitar, and all the jazz players think that’s the way you play, and the rock players that’s what. And they’re all particular styles which employ the guitar. They take this bloody thing, this box with strings on it, and they use it in a particular way which suits their purposes. Well, that’s all I wanted to do. I wanted to take that box with strings and use it in a freely improvised situation. And it wasn’t any good, as far as I could see, playing it like a rock player, for instance, and so on. And that description makes it sound quite calculated. But that was a realization that happened over years. In each situation, it wasn’t appropriate to use any of the inherited language, if you like, or technique. It was of some use, but it didn’t seem to be of much use. So there was all that. I was trying to use the instrument as I thought in a more appropriate way.

Another thing that led me to playing solo was the problem of volume. I didn’t see how I could really play with anyone else except maybe another guitar player. It wasn’t that I wanted to work at such a very low volume level, but I wanted to work – particularly at that time – with a wide dynamic range over a short time space, shooting around a lot, up and down. And that’s got interesting possibilities within a group context. But I wasn’t at that time working in a group that was accommodating that type of thing, except possibly “Iskra.” And even in a group like that, where everyone used this fast dynamic fluctuation, there were still certain contradictions; but I think it did at times work very well in that group.

By 1971, it seemed that groups were settling down to a sort of early middle-age period. Most groups by then had been going since the early-middle Sixties. I’ve always felt that an improvising group – it’s only a suspicion, I can’t prove it – but my suspicion is that a lot of improvising groups change quite radically after two to three years. After a couple of years it gets into the sort of thing I’m less interested in, although it’s the sort of thing I’ve gotten into playing solo, and that is playing as an identifiable group, playing a music that is identified with the group. So you get these long term things – there’s been a lot of them in Europe. I think the longest is Han Bennink and Misha Mengelberg who have played together about 57 years. Or John Stevens and Trevor Watts they’ve gone on for a long time and they’ll likely go on forever. Well, that’s fine, and they’ve obviously found it a satisfactory way of working.

Steve Beresford | Derek Bailey | Uithorn, Holland; 1977 | ICP’s 10th anniversary festival. Photo: Gérard Rouy

Yet it always seems to me that after a certain time most groups like that do get into a different type of playing, and for most of them that’s the kind of playing they want to get into. The music becomes much more identifiable, identified with them, and sometimes with a certain idiom – maybe free jazz, funny music, circus-like humor, whatever. They have an identity, and they work within that. Now that’s what doesn’t interest me about a group. At that point, I lose interest in the group. So at that time I was in the “Music Improvisation Company” and I was in “Iskra 1903” and also playing occasionally with Tony Oxley and with the Spontaneous Music Ensemble (S.M.E.); and they all became like that to me, the S.M.E. particularly.

HENRY KAISER: DO YOU THINK THAT’S BECAUSE JOHN (STEVENS) HAD THE SAME SORT OF PROBLEM AS YOU, BUT HE SOLVED IT IN A DIFFERENT WAY BECAUSE HE WAS A LEADER OF A GROUP (THE S.M.E.), SO HE CHANGED THE GROUP TO FIT HIS NEEDS?

Derek Bailey: Quite possibly. John’s a very special case, you know. He’s a very rare figure in this music. He’s a very good musical organizer, and you don’t get good band leaders in this sort of music. So John’s a very special case. But, still, I think he was probably doing the same as most of the regular groups in that he was establishing a music centered around him and Trevor after a while – although I think that was largely based on music that he and Evan used to play in ‘67. But that’s a long story.

HENRY KAISER: WHY DO YOU THINK AT THAT TIME THAT PEOPLE HERE AND IN GERMANY AND HOLLAND WANTED TO GO TO THOSE DEGREES OF MUSICAL FREEDOM WHEREAS MUSICIANS IN OTHER AREAS – IN THE U.S., SAY – HAVE NOT REALLY DONE SO?

Derek Bailey: We didn’t have a music here. We had the great advantage of not having a music, in England particularly. In the U.S. you have jazz and rock. I mean, we had rock here, but no one had taken it that seriously. Now it’s somewhat different. But there wasn’t any question of having to play anything, you see. I mean, the fact that you could go out and play nothing was a great relief. You could go out and play nothing, and someone would say, “What the fuck was all that?” – and that was fantastic. Because they couldn’t come up and say, “Oh, you sort of play like Jim Hall a bit.” To have someone come up and say, “What the fuck are you doing there?” was a great relief.

But the whole thing about free improvisation coming up at certain times – I wouldn’t try to sell this idea to anybody, but I believe it’s always been present to some extent. I think the idea of improvising freely is such a simple, attractive idea that people must always have tried it. The first band I ever heard doing it was in 1956-57. I played with them a couple of times and hated it. I was too busy trying to get the instrument together in a certain way. I knew that band for a year or two and they were largely a freely improvising band, and that was in the middle-Fifties. And I don’t think that’s unique or anything. I think that possibly you could find somebody who knew of some other free band in another provincial town in England or anywhere else. So I think this is something that’s always been floating around. It’s such an obvious, logical way of making music for people who don’t have an axe to grind or a career to pursue.

Now the solo thing – well, there was that thing about groups. It seemed to me that by that time most of the groups had gotten themselves established. They sounded like a certain thing, and they played in a certain way. They had gotten an identity and worked within that identity as a unit. And I think most of them are quite aware about that. They use it as a springboard. In a way that’s how a lot of jazz musicians prefer to work. Familiarity leads to better results, but results in a certain direction. Anyway, I didn’t find that appealing to me. As soon as I’ve been in a group a couple of years, I usually want to get out of it. The only exception to that was the “Music Improvisation Company,” but that was an extraordinary group anyway, and it sort of exploded after three years. It disintegrated. I mean, we were all going in different directions anyway, and – strangely enough – we drew strength from that. I liked that group very much.

Steve Beresford | Derek Bailey | Uithorn, Holland, 1977. Photo: Gérard Rouy

HENRY KAISER: DO YOU MEAN THAT WHAT YOU LIKED ABOUT IT WAS THAT THERE WERE ALWAYS A LOT OF SURPRISES?

Derek Bailey: It never had any single identity. We didn’t play very often, and when we played the only thing you could be sure of was that it wouldn’t sound anything like the last time we played. The thing about that group was it was five-piece for its last two years, and it had five leaders. I don’t mean that we competed for leadership, but there were five people who had a completely different idea of what the group should do. And it seemed that any of those five people could establish their influence over the rest of the group, because very often the group would behave the way one guy wanted it to behave. Now that might last for three months and then it would change, but then again it might change from week to week. I’ve never been in a group like that. It was extraordinary. And the people in it were quite different. I mean, the difference between Jamie Muir and Hugh Davies was complete in a musical sense. They belonged to two different ends of some musical scale, with Jamie at one end and Hugh at the other. And yet we worked together within that group OK. I say OK – I mean, there was a lot of friction in that group, but I’ve never known a successful group without friction.

But after a certain period, I was no longer interested in playing in a group; but I was still interested in playing with other people, as I am now. And I thought that one of the best advantages of playing solo – and this is one of the things that really advanced the idea for me – was that I could play with anybody. If I had been working regularly in a group – I mean, there are certain loyalties and associations. Generally speaking, someone who works in a group just works in a group. They might occasionally play with another group, but the scope of their playing as regards playing with other people is usually limited to that group and its immediate associates; while if you’re playing solo you can play with anybody who’ll play with you. And I do play with anybody. I mean, I’ve heard the accusation that anybody who plays solo leads a sort of self-centered musical existence, and that might be right, and I don’t necessarily see anything wrong with that. But in my case, it’s not really applicable. Because I’ve played with more different people since I’ve played solo than before I played solo.

HENRY KAISER: DO YOU FIND PLAYING SOLO, THEN, A BETTER WAY TO DEVELOP YOUR MUSICAL IDEAS?

Derek Bailey: I like working solo – for that reason, and for the reason that I needed to develop some self-reliance in this music. If you’re going to go make a solo improvisation, you’re in about as isolated a musical situation as you can find, I would have thought. To play solo is nothing, but to improvise solo is a pretty demanding situation. So there’s a lot of attractions to the situation, but one of the main ones is that in that situation I can play with other people regularly or occasionally.

Now one of the disadvantages of playing solo, and there are quite a number, is the same as that with the regular groups. I’m going around playing an identifiable music. I go around and play some sort of strange guitar most of the time. But that is not what I’m interested in in playing solo. I am not interested in demonstrating the way I play the instrument. But I guess that most of the gigs I get I get because somebody wants me to come along and demonstrate the way I play the guitar. That side of solo playing doesn’t interest me at all. I mean, I suppose that’s probably what I do on most gigs. But I consider if I’ve finished playing and I feel I’ve done only that, then I think I’ve played very badly. And it can happen that way, unfortunately.

Steve Beresford | Derek Bailey | Tristan Honsinger | Akademie der Künste, Berlin1978. Workshop Freie Musik. Photo: Gérard Rouy

HENRY KAISER: WHAT WOULD YOU LIKE TO BE DOING?

Derek Bailey: To improvise, whatever that means at that particular time. I mean, it might sound pretty much the same as last time, but it isn’t.

HENRY KAISER: DO YOU MEAN IMPROVISING TO YOUR SATISFACTION OR SHOWING THE AUDIENCE SOMETHING ABOUT IMPROVISATION BESIDES SHOWING THEM SOMETHING ABOUT PLAYING THE GUITAR?

Derek Bailey: I’ve never been sure about audiences. I’ve never understood what the responsibility of a performer is to an audience. It’s intensely complicated. When people talk about audiences, they usually drool on about communication. Anyone interested in communication should spend time digging holes for telegraph poles.

There’s much more going on between a performer and an audience than just communication. I don’t know what happens but I think that the audience’s role in listening to improvising – and I never liked saying anything about audiences because if anyone asks what I think about an audience, I’m just grateful there is one – but actually I would think that an audience listening to improvisation has a greater responsibility than any other type of audience because they can affect the musical performance in a direct way, in a way that no other audience can affect the musical performance. They can affect the creative process in every aspect. Every aspect of the music, every part of the process can be affected by the audience if it’s improvised music because the whole thing is going on at the time they’re witnessing it. They’re witnessing the whole process of producing that music. I mean, there’s a lot of work behind it, and they’re not going to affect that, but they can affect the immediate production of the music, its immediate construction, which is the crucial time for improvisation.

HENRY KAISER: IN OTHER WORDS, WHAT THEY CAME TO HEAR IF THEY’RE INTERESTED IN IMPROVISED MUSIC?

Derek Bailey: Well, that’s right. But I don’t know how many people are interested in it. I mean, if they’ve come to hear somebody play the guitar in a certain way, they may not be interested in improvisation at all. But I think of what I do on the instrument as entirely associated with improvisation, so I would have thought that anybody who’s not interested in improvisation couldn’t have been very interested in the way I play the instrument anyway. Because I play the instrument in a way that I think is appropriate to non-idiomatic free improvisation. And that’s the hardest job of all – to keep it open-ended. That again ties up with the technique of playing the guitar. And the same applies to the music. The two, it seems to me, have to be complimentary all the time. The technique, the way you play the guitar, all of it should be prepared for some movement or change. And the same thing applies to the music. And if at some point you no longer move it along, and this applies either to the instrumental playing or to the music, which are inextricable, completely entwined – if you arrive at some point where it isn’t moving along, then you’re finished as regards the things we’re talking about. Then maybe you’ll do something else. Maybe then you’ll just specialize in playing the guitar in an odd way or playing whatever has become identified as the music you play. Then it’s possible you’ll become so interested in that that that is the end, the end you’re pursuing; it might still be a viable activity, but you can’t call it, it seems to me, free improvisation.

I mean, I’m not so interested in these labels. They are a nuisance. But it does imply something: free improvisation is an area in which you can do all sorts of things. You can go in it, find out the music you want to play, bring it out and play it. And that’s what most people do. That’s what most groups do. They settle down, things start working, then they’re out and they do it, and that’s that. Then occasionally they dip back in to get another member or something, make one or two changes.

The younger guys in London at the moment – actually, apart from me, most of the older guys are still quite young – have a good idea, and it’s very frustrating to the older guys. The idea is that you don’t have set groups. You never see them in the same group twice; or, if you do, in between times, they’ve played in another thirty combinations. It’s just a mix. That’s a free improvising community, and it works like that.

Now that’s the sort of thing that was happening in the S.M.E. around 1967, but not to the degree that the musicians are doing it now. Now, to a lot of musicians, I think the majority, that’s not a satisfactory situation. They do want a music they can get hold of. They want to work on it and go out and play it and show people that it’s good music. And there’s nothing wrong with that at all. I’m not trying to put that down. But the situation I find interesting is that free one, and I wouldn’t want to work in any other way. But I can understand somebody either dabbling in it briefly or not wanting anything to do with it. I mean, the freedom in free improvisation might be just this – that you can take out of it what you want, and you don’t have to stay. But I’m interested in it as a way of working permanently. For one guy in a basic situation of working on his own with an instrument, I think it’s the only way to work. Or, to put it differently, free improvisation makes it viable for one guy to work with one instrument on his own.

But the possibilities are so enormous in free improvisation that I think most people would prefer to back off from it. I know a guitarist, a flamenco player, who’s interested in free improvisation, but he would never play it. He goes and maybe listens to it occasionally and talks about it, but what he wants to play is flamenco. Or I don’t think you could talk to Sonny Rollins about free improvisation. Sonny Rollins is interested in free improvisation in so far as it has some use for his purposes as a conventional black jazz player.

I can understand that absolutely. I mean, he’s a great jazz player. He has a lot of music to play, and he’s going out and playing it and that’s fine. If he can do that for the next twenty years -he’s already done it for twenty years – then he’s done alright. There’s nothing wrong with it. However, there is still the whole of this field of free improvisation to work in, and I think the possibilities are greater there than in any other sort of music.

Misha Mengelberg | Johnny Dyani | Derek Bailey | Tony Oxley | Leo Smith | Maurice Horsthuis | Terry Day | Company, London 1978. Photo: Gérard Rouy

HENRY KAISER: HOW DOES PLAYING WITH DIFFERENT GROUPS OF PEOPLE INTEREST YOU THEN?

Derek Bailey: Well, for different people, it might work differently, but my main interest in playing with other people is their music. I find I’m very affected by people I play with. There are times when I’m not, but usually that’s when I don’t like the music. Actually, whether I like it or not, I’m usually very affected by it. I mean, the difference between playing with Han Bennink and with Anthony Braxton is considerable, and they each take me to musical areas I might not get to on my own. That’s not the only interest I have, but that’s one of the things.

HENRY KAISER: WELL, THE STEVE LACY ALBUM, CRUSTS (EMANEM 304), SEEMS TO BE A VERY DIFFERENT KIND OF SITUATION FOR YOU BECAUSE THEY’RE ALL PLAYING TUNES, AND YOU SEEM TO BE DOING SOMETHING FAIRLY DIFFERENT, WEAVING IN AND OUT.

Derek Bailey: Well, I’m interested in that kind of a situation: in going in and being as complimentary as possible. I don’t want to go in and, in spite of everything, play what I always play. But I’m still not going in there and imitate or take on some other identity in order to be complimentary. So I’m interested in the way they affect my identity, if that’s not too opposite a way of putting it.

HENRY KAISER: WHEN LACY ASKED YOU TO COME ALONG, DO YOU THINK HE ASKED YOU EXPECTING YOU TO DO SOMETHING PARTICULAR, KNOWING WHAT YOU DO? DID YOU DISCUSS A LOT WHAT YOU WERE GOING TO DO AHEAD OF TIME?

Derek Bailey: No. I mean, those are quite carefully arranged parts, and they rehearsed them. But I didn’t actually have a part, because Lacy doesn’t have guitar parts. He has piano parts. So I had the piano part, but I didn’t actually play it. I’ve played his music, though, in some other situations – in a trio, for example, with Misha Mengelberg, me, and Lacy. I like his music. He’s a very strong musician. But, in general, that’s all I could say about that. I mean, I don’t mind playing in any situation at all. The only people I would not want to play with are people who don’t want to play with me, who are afraid I might upset something they want to do.

But I wouldn’t think that the way anybody plays is any good unless it’s open-ended, unless it allows them to play with almost anybody. Whether other people feel they could play with me, I don’t know. But I wouldn’t worry if they were playing tunes or whatever. I’d be very interested in finding a way to make it work. And if I couldn’t find a way, then I’d consider that was something I had to do something about – because I think any way of playing should be, if not necessarily all inclusive, at least have a certain openness to playing with other people, particularly other people whose music you enjoy.

Misha Mengelberg | Johnny Dyani | Derek Bailey | Tony Oxley | Leo Smith | Maurice Horsthuis | Terry Day | Company, London 1978. Photo: Gérard Rouy

HENRY KAISER: DO YOU OFTEN TALK MUCH ABOUT THE MUSIC BEFOREHAND, IF YOU’RE PLAYING WITH DIFFERENT PEOPLE? DO YOU THINK, IF YOU DO, THAT THE IMPROVISATIONS ARE MORE SUCCESSFUL?

Derek Bailey: There’s a lot of discussion about that, whether it’s useful or not. I don’t think it’s always necessary.

HENRY KAISER: WHAT ARE THE USUAL POINTS OF DISCUSSION IF YOU TALK ABOUT IT?

Derek Bailey: I don’t know. I think usually you’re just trying to establish some sort of personal relationship or to reassure each other. I don’t know how useful it is. Then again it could be harmful. I know people that I can play with, but I can’t talk about music with. We disagree. Han Bennink and I are like that. If we were to discuss any piece of music, I think we’d take diametrically opposed views. But I think we can play with each other OK. But then if we discuss music, I think we usually find out that we hold opposite views on almost any aspect of music, or on many aspects of music. So what does that prove? I think it proves that a discussion of music is only part or is some parallel activity to playing, an activity that might have correspondences with the business of playing but is actually a totally different thing. It’s just a parallel structure, and occasionally you can shoot lines across and say that that’s referring to that. But they’re not the same.

HENRY KAISER: I WONDER HOW YOU FEEL ABOUT THE DUTCH IMPROVISERS? A LOT OF THE STUFF THEY’RE DOING SEEMS KIND OF STRANGE, THE MUSICAL JOKES AND SUCH.

Derek Bailey: Well, they use a sort of collage. And they’re very influenced by composition. I mean, in my view, it’s sort of unfortunate. But they are influenced by composition. And one of the fashions in composition in European avant-garde circles in the last few years is that whatever music you’re into, it will allow you to write these pretty melodies – whether it’s political music, theatre music, circus music, systems music, whatever. It’s been very prevalent in European avant-garde circles for about five years now, back to the melody. And in England it takes the form of a sort of cozy Sunday evening Edwardian-type drawing room music. Like Gavin Bryars’ music, for instance. Or Christopher Hobbs’. They call it experimental music, and it allows them to work with melody. The Dutch improvisers too are very influenced by composition; partly because Misha Mengelberg and Willem Breuker are both composers actually. They’re fine improvisers as well. But they are still governed by pre-determined statements and concepts.

HENRY KAISER: DO THEY STILL PLAY FREELY VERY MUCH?

Derek Bailey: Well, they do play freely, I would say. But you have to appreciate these guys from a composition point of view: they have a number of points, predetermined points, that they’re going to make in a musical performance. There’s that whole composition view of things.

HENRY KAISER: BUT DON’T YOU HAVE THAT TOO? IF YOU’RE WORKING ON CERTAIN MATERIAL, THEN YOU’RE GOING TO BE PUSHING CERTAIN THINGS AHEAD.

Derek Bailey: Somebody might take that interpretation. But I don’t have a specific point to make when I go to make a performance, any more than I have a point to make if I play here at home. And that’s one of the differences between composition and improvisation, in that each composition usually has a definite, clearly defined, pre-decided point to make. Improvisation is not much use for making statements or presenting concepts. If you have any philosophical, political, religious or racial messages to send, use composition or the post office. Improvisation is its own message. But now in Holland there are some newer players: Maarten van Regteren Altena, Michel Waiswich, and the cellist Tristan Honsinger who, together with Han, have, I think, brought a freer approach to playing over there. But there is room for many approaches to improvisation, and I think that what Misha does is very interesting. And it’s getting more interesting.

Derek Bailey | Leo Smith | Tony Oxley | Johnny Dyani | Company Week, London 1978. Photo: Gérard Rouy

HENRY KAISER: GOING BACK TO SOLO IMPROVISATION, I’VE NOTICED THAT YOUR WORK ON THE FIRST SIDE OF INCUS 2 IS VERY DIFFERENT FROM THAT ON LOT 74 (INCUS 12). HOW QUICKLY DOES YOUR PLAYING CHANGE?

Derek Bailey: Well, there aren’t any radical jumps. I’m never quite sure what’s happening at the moment. It seemed to me there was quite a big change that happened to me two or three years ago. But the big changes don’t interest me that much. If they happen that way, then they happen. I think maybe at the moment there’s been a sort of change. I’m not sure about that, but I’ve started playing a lot more acoustic. So the electricity’s gone out of it almost entirely, and when I’m playing electric, it’s at a pretty low volume level. Just high enough to be present in the two speakers. All I use them for is to get rid of that stationary thing which I don’t like about electric music, any electric music, that beady eye or speaker eye – the point source. And as long as there’s some kind of mix going out – I don’t know exactly what it is – that’s fine for me. So I just sort of keep things moving around. I mean, I try a lot of different things. I have sort of exercises for the feet.

HENRY KAISER: A GUITAR PLAYER WITH EXERCISES FOR THE FEET?

Derek Bailey: Well, you can get certain effects. When I say effects, I mean aural effects. Like there’s a way of playing fast single note things with a slow movement that has a certain type of effect that’s quite strange. It has an effect or it appears to have an effect on the movement. I mean, playing fast single note things and moving your feet very slowly is not very easy as regards your limbs. Physically, it’s a bit awkward, it’s difficult; to put it to a finer point, it’s fucking hard! And the opposite is difficult – that is, playing slowly and moving your feet quickly. As everyone knows, there’s a synchronicity between things. And it particularly comes out in instrumental playing.

There’s a guy – Curt Sachs – an old German musicologist, dead now, but he’s written some interesting stuff about ethnic music; he’s written some interesting stuff about everything really. And he locates two centers – he calls them mind centers, but they are two general centers for producing music. And one he associates with song – the voice, and the other he associates with dance which is instrumental music. And he makes this point, which I like very much, that instrumental music’s got nothing to do with song at all. I mean, there’s this big thing you hear about every instrument, like making the piano “sing” and the violin “sing.”

HENRY KAISER: TO TRY TO BE A VOICE.

Derek Bailey: That’s right. And one of the main objectives of a lot of instrumentalists is this voice-like music. And it’s considered a desirable thing to have this approximation of the voice. But he produces this argument that playing an instrument has absolutely nothing to do with the voice at all. It doesn’t use the same nerve centers, mind centers, whatever you like. He makes this point that it’s all associated with physical movement, the dance largely. And I like that very much. And you can hear it in free improvisation, though he’s talking largely about ethnic music. And he puts in this description about drummers; like most drummers, the way they play is dictated just by where the drum is. What do the feet do? The feet might not be making any sound at all, but the feet are going like mad when they’re playing. And possibly, depending on whether the ground is wet or whether it’s dry effects what they play on the drum. And I can see that entirely. And you can hear it.

In free improvisation, you get this purely physical – and I don’t just mean the sort of heavy German physical strength type thing, but like the nervous system taking over. Now, allying that sort of natural instrumental drive which is associated with the dance to a deliberate control of all four limbs in a particular way is a strange thing to do, you know; to not lose that feeling, that sort of “up there” feeling for about thirty minutes, the tenseness, committedness, that involvement, whatever it is – and yet still be trying to do something with absolute control. And I have one or two exercises for that type of thing which has to do with waggling feet and doing certain things on the instrument.

HENRY KAISER: I WANTED TO ASK YOU ABOUT SOMETHING YOU SAID IN THE LLOYD GARBER INTERVIEW (IN GUITAR ENERGY, 1972) AROUND THE DISCUSSION OF NON-TONALITY. YOU SAID THAT IDEALLY IF YOU PLAYED TWO NOTES, THERE WOULDN’T BE ANY POINT OF CONNECTION, EXCEPT IN SO FAR AS THE NOTES FOLLOWED FROM EACH OTHER IN TIME. WHAT KIND OF INTELLECTUAL WAYS DO YOU TREAT THE GRAMMER OF WHAT YOU DO, THE CONTINUITY OF IT, THE LINEAR OR LONG MOVEMENT?

Derek Bailey: Well, I don’t think the grammar lies in the pitch.

HENRY KAISER: DOES IT LIE IN MENTAL ASSOCIATIONS OF DIFFERENT KINDS OF SOUNDS?

Derek Bailey: It lies in the sort of musician you are. It’s like everything you know about music or would like to know about it, and what you know about the instrument. I mean, some of it will be in the instrument, some of the structure, if you like.

HENRY KAISER: HOW SO?

Derek Bailey: It’s to do with this instrumental impulse we were talking about, Curt Sachs’ instrumental impulse, that if you’re playing an instrument in a certain way that’s got a physical side to the playing of it – that is, it’s not just two wires plugged into your brain, there’s a whole physique about it, you use both feet, both hands – then many times there are going to be occasions where there are physical continuity things. They’re all variables, of course. But if you play two notes, for example, in very quick succession, then probably you’re going to play the third note in quick succession; and that’s more than anything a physical thing. If you played the third note after a gap – if you play a sequence of notes with a very differentiated spatial relationship – then that’s probably less of an instrumental thing.

Derek Bailey playing the big banjo | Maurice Horsthuis | Company Week, London 1978. Photo: Gérard Rouy

HENRY KAISER: WELL, IF YOU’RE GOING ALONG, AND YOU PLAY A LINE WHERE THERE ARE A LOT OF FAST NOTES, BUT ALL OF A SUDDEN YOU THINK A THOUGHT, AND YOU DECIDE THAT THIS TIME THE NEXT NOTE WON’T BE A FAST NOTE, THEN I’M WONDERING IF THERE’S SOME KIND OF PARALLEL TRACK RUNNING ALONG WHERE AN APPRECIATION OF THE MUSIC MAKES YOU DECIDE, “WELL, THIS TIME I WON’T DO THAT,” OR “I’LL DO THIS ABOUT FOUR TIMES?” THIS IS NOT A PURE MOTIVE THING, BUT I’M WONDERING WHAT KIND OF INTELLECTUAL RELATIONSHIP EXISTS?

Derek Bailey: Does anybody play like that? What you are asking for, I think, is a definition of improvisation. I don’t know one. Decision making for the improviser comes, I suppose, out of a joint meeting that takes place at the time of performance between his musician ship, his memory, his intuition, his relationship with the instrument, his intellect, his outellect, his undellect, and about 1,000,000 other things as well. (Did I mention the pills?)

I find it very difficult to think of a situation where everything you play is decided intellectually, in a conscious way. But it plays its part. Its influence might melt in all the time. And I would think that when you’re playing badly, it plays a very strong part. It really surfaces. But you can work on that sort of thing. You can work on those situations where nothing’s happening – employing a technique, for example, where you alter the degree of control you have over the technique; introduce an aleatoric element.

A device I use sometimes is to play something quite nothing – sloppy would be a good word – then try to figure out what it was. So then you slow it down a bit and try to look at what it would have sounded like if you had played it properly. It’s deliberately very indeterminate. There are also certain things I find very difficult to control, like some of the noisy things. I don’t know exactly what they’re going to sound like when I play them. A little trick I’ve been working on lately is sliding the pick on the side of the string, which can produce a high scream. It may not work at all, and the pitch is totally unpredictable. And there are quite a lot of things like that where you can’t tell exactly what the result is going to be. So you can move into those things. I prefer them to silence. Anyway, I believe Cage has a copyright on silence.

HENRY KAISER: DO YOU TEND TO TAKE SOME SPECIFIC KIND 0F ALEATORIC TECHNIQUE AND THEN GO INTO SOMETHING LIKE THAT?

Derek Bailey: No, not specifically. I just think it’s part of the technique. I would expect to have it in the technique, anyway. I mean, usually I get suspicious of things you can do best. When you can do something really well, that’s when it gets more or less no good to you. Because you know exactly what’s going to happen the moment you start it. You’re just going to do it. And there are some things I’ve never gotten the hang of and those are the things I quite like. I’ve been playing them for years, and I’ve never had complete control. I mean, I know exactly what’s happening. But I couldn’t produce the same thing twice doing these things. As soon as I can, I’ll stop playing them. But some things, I know what’s going on all the time. They’re patterns really. I may as well be playing licks. But they’re useful in that they form the basis of the language and you can get some impetus going from them. You can keep the thing moving along like that. But it’s in other areas where the music can carry on, where you can be in it. Those are the areas where the work is – unless you’re going to be an improviser in the pure sense and never get the instrument out of the case except when you go on the gig. I have another guitar I do that with.

HENRY KAISER: DO YOU HAVE CONSCIOUS PLANS TO STAY WITH THE INSTRUMENT AND TO STAY WITH THIS INDEFINITELY ON INTO THE FUTURE? DO YOU HAVE ANY GOALS YOU’RE WORKING TOWARDS?

Derek Bailey: I don’t have any plans to give up. I retired, though, a long time ago. I used to be a commercial musician – for ten years. That’s when I retired. I retired out of an interest in music.

Evan Parker | Derek Bailey | Tristan Honsinger | Tony Coe | Lindsay Cooper | London 1980. Photo: Gérard Rouy

http://henrykuntz.free-jazz.net/

More Derek Bailey in Prepared Guitar Blog

More Derek Bailey in Prepared Guitar Blog